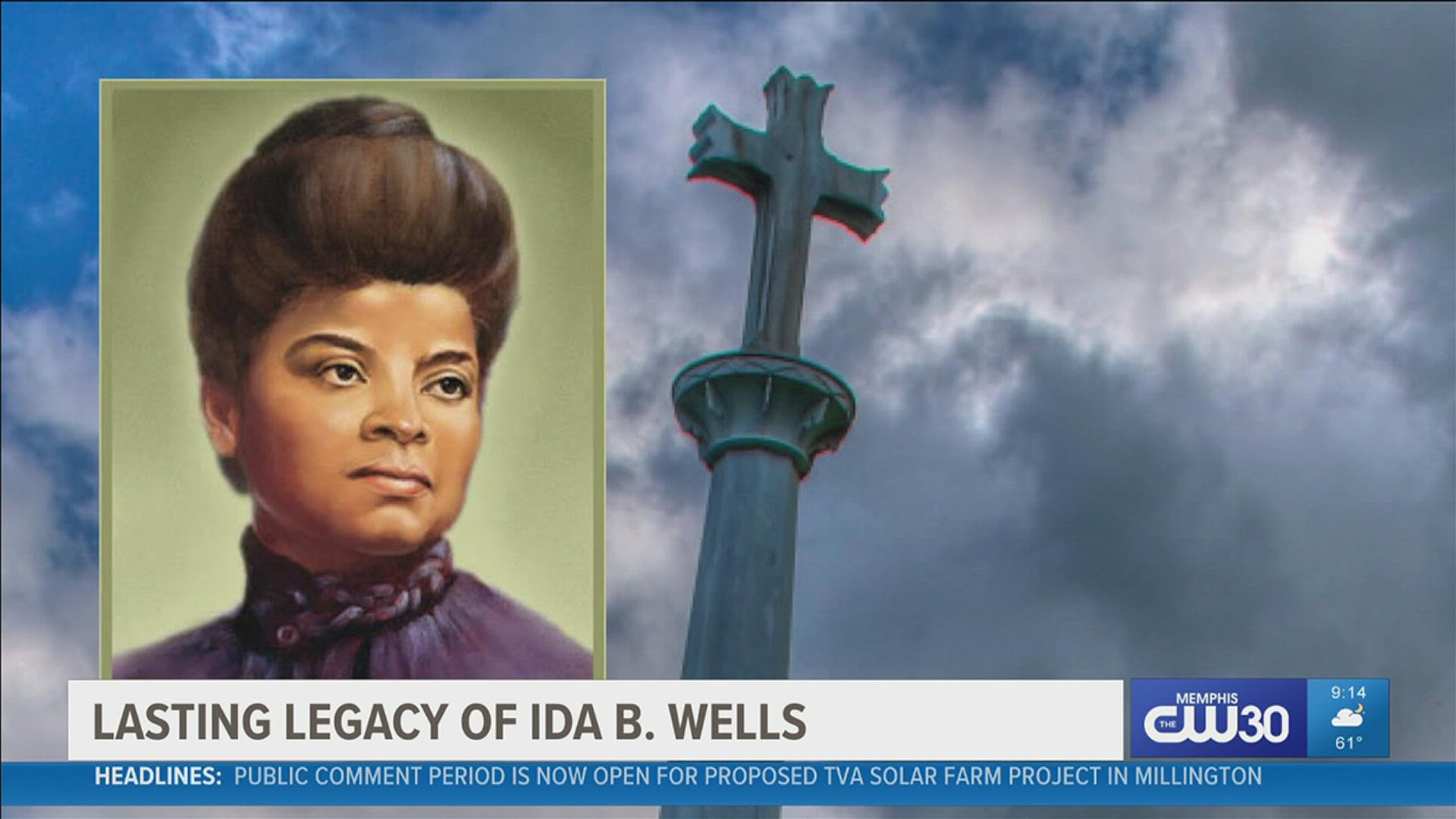

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Ida B. Wells is women's history.

"When I think about her courage, it's unparalleled," Wells' great-grandson, Daniel Duster, said.

She was an investigative journalist, educator, and civil rights leader.

Wells was born into slavery in Mississippi in 1862 and after the yellow fever killed tens of thousands of people, including her parents, Wells' passion for fighting against inequality ignited from within.

Duster said she eventually moved to Memphis where she became a school teacher.

"She did freelance writing at that time and wrote an article talking about the school systems and the disparity between the white school systems and the black school system," he said.

He said the white school system had adequate funding, proper class sizes, and resources while the African-American school system was overcrowded, underfunded and didn't have the resources.

"She did not get fired, but they did not renew her contract the next semester," Duster explained.

It forced her to find employment elsewhere after becoming a lead editor and co-owner with the Memphis Free Speech, she discovered an issue she needed to look deeper into: lynchings.

After losing three of her friends who owned the People's Grocery, she wanted to make people aware of all that was going on.

This happened 130 years ago just north of downtown.

"Reading what transpired afterward, it was these thugs did this and they didn't say thugs, but that was the terminology that was used. It was like these thugs rose up against white people and a conspiracy to kill white men. She said, wait, I know that if they're saying that about these people and I know they're upstanding men in the community, what about all these other lynchings that have happened? So she really became America's first investigative journalist," Duster said.

Wells was forced to flee Memphis after she printed the truth about their lynchings. Duster expressed his respect for his grandmother.

"For her to stand up in the face of adversity with death threats, and she didn't return to the South for literally decades," Duster explained. "She feared for her life, but she stood up against those odds and was willing to go to jail and suffer whatever consequences necessary to fight for justice."

Decades later, Wells has received recognition across the country for her contributions.

On Monday, Memphis city leaders renamed 4th Street between E. H. Crump Boulevard and Union Avenue after Wells.

Duster said if she were still alive today, she would be honored, but there is still work to be done.

"There's still overt racism, there's still systematic racism, and she'd say thanks for the honor, but let's address these problems," Duster said.

He will also visit the White House on Tuesday to witness the signing of the Emmett Till Anti Lynching Act, which will make lynching a federal crime and will allow cases to be investigated at a higher level.

Duster said leaders denied the act three times prior to now.

"If a murder is investigated locally, then you get local resources, so if I am a sheriff and I go fishing with the person who did the lynching and that's my cousin and nobody's going to jail," Duster stated. "Literally of the almost 5,000 documented lynchings, I'd suggest that there's probably 3/4 or five times that. Literally, almost nobody went to jail and so if it were a federal crime, you'd get federal resources and do the investigation."