MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Problems with rape kit evidence testing keep haunting Memphis.

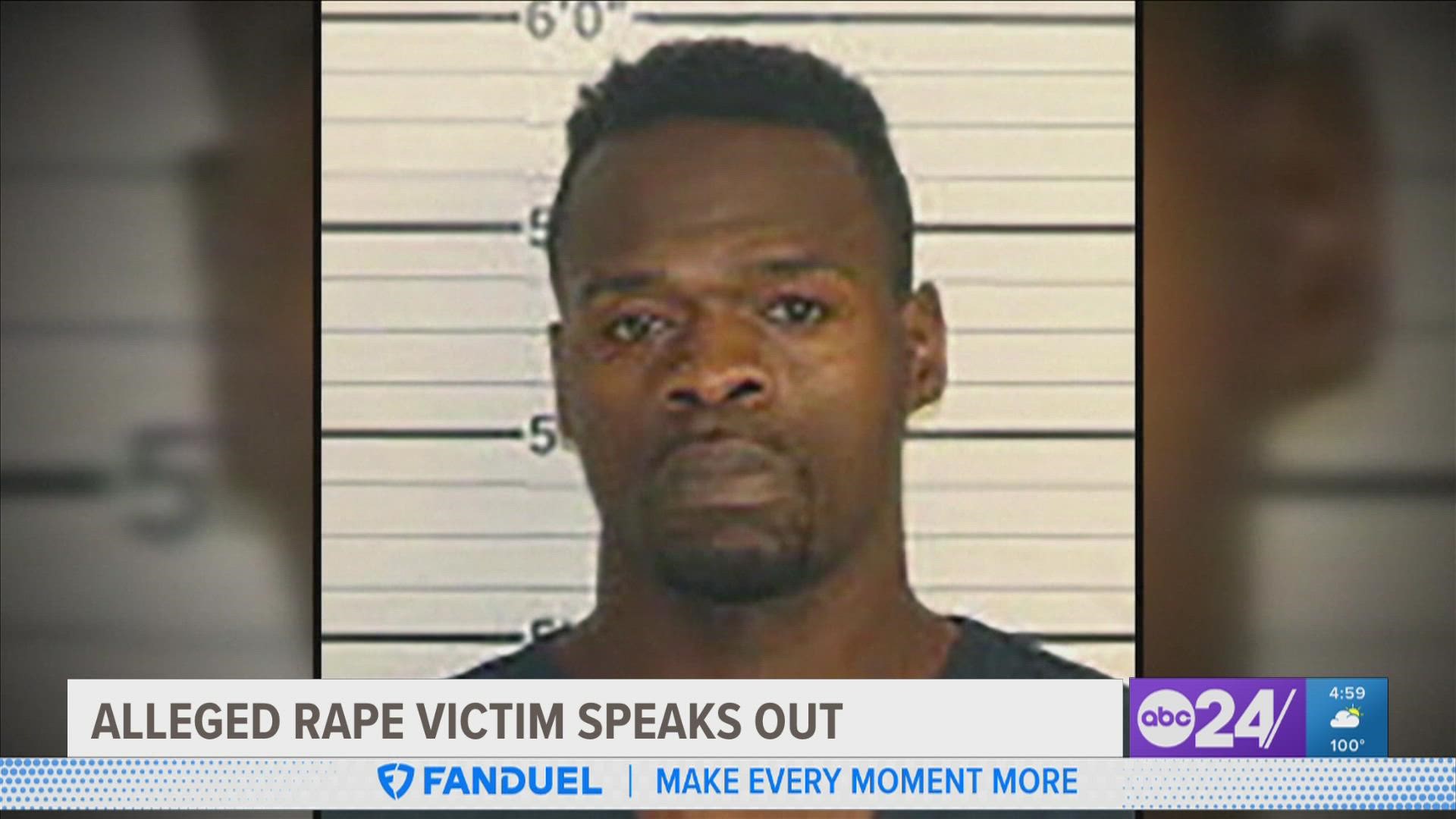

A city long plagued by a heavy backlog of untested sexual assault kits was shaken by Cleotha Henderson's arrest in the killing of Eliza Fletcher after she was abducted during a morning jog last month.

So when authorities said his DNA was linked to a rape that occurred nearly a year earlier—charging him separately days after he was arrested in Fletcher’s killing—an outraged city turned to the obvious question: Why was he still on the streets?

The case of Henderson, who already has served 20 years in prison for a kidnapping he committed at 16, has reignited criticism of Tennessee’s sexual assault testing process.

That has included calls for shorter delays from the testing agency, the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, and questions about why Memphis didn't seek to fast-track a kit that could have been tested in days.

Instead, it took nearly a year, unearthing key evidence too late to charge Henderson before Fletcher’s killing.

The tragic outcome brings back memories from the early 2010s, when Memphis revealed a backlog of about 12,000 untested rape kits that took years to whittle down and led to a lawsuit that's still ongoing.

The new rape charges have spurred another lawsuit accusing the Memphis Police Department of negligence for the delay.

The scenario also has raised broader concerns about Tennessee's struggles with a problem that has been in the national spotlight for decades and that some states have addressed.

In response, GOP Gov. Bill Lee and Republican legislative leaders have fast-tracked money for 25 additional TBI lab positions, including six in DNA processing. The agency had requested 50 more this year, but Lee funded only 25 in his proposed budget and lawmakers approved that amount.

Meghan Ybos, a rape victim involved in the backlog lawsuit, blames the city for not curbing a problem known for years despite receiving more than $20 million in grants to address the backlog.

“I don’t think the shortcomings of Memphis law enforcement are limited to the handling of rape kits," Ybos said, "but I think the public should be outraged at the lack of transparency about what Memphis has done with tens of millions of grant money that the city and county have received to test rape kits, train police, hire victim advocates, prosecute cold rape cases and more.”

As of August, Tennessee's three state labs averaged from 28 to 49 weeks to process rape kits under circumstances that don't include an order to rush the test. More than 950 rape kits sat untested in labs.

TBI attributed the delays to staffing woes and low pay that complicates recruiting and keeping scientists.

TBI Director David Rausch laid out further moves in hopes of processing all evidence in eight to 12 weeks within the next year: Overtime, weekend hours, more outsourcing to private labs and using retired TBI workers for new worker training to free up current employees.

Tennessee doesn't require specific turnaround times for newly collected rape kits, though 19 other states do, according to the Joyful Heart Foundation, which is pushing Tennessee to follow suit. Massachusetts requires processing kits within 30 days, but most of the states require testing within 60, 90 or 120 days.

Tennessee's House and Senate speakers haven't flagged turnaround mandates as a priority. TBI, meanwhile, said any turnaround requirement would need proper funding.

Ilse Knecht, policy and advocacy director for the Joyful Heart Foundation, said Tennessee's problems aren't unique. Without an official U.S. count of rape kits awaiting analysis, Knecht estimated there are likely more than 200,000 untested kits in law enforcement or hospital storage nationally.

“Every single one of these kits that is sitting on a shelf could represent someone like the offender in this case, where you look at their criminal history and they’re committing all kinds of crime, they’ve been doing it for decades, and the evidence that could stop them is sitting on a shelf somewhere,” Knecht told The Associated Press.

Henderson was charged with first-degree murder in the kidnapping and killing of Fletcher, a mother of two and a kindergarten teacher who was on a pre-dawn run Sept. 2 when she was forced into an SUV on the University of Memphis campus. Her remains were found on Sept. 5 behind a vacant Memphis house.

Henderson, who also has gone by Cleotha Abston, has not entered a plea in the killing but was rebooked in jail on Sept. 9 on charges related to the September 2021 rape of a Memphis woman. Henderson has pleaded not guilty to charges in that attack, including aggravated rape.

The new lawsuit brought by the woman who says she was raped in that attack says Memphis police could have prevented Fletcher’s death if they had investigated the 2021 rape more vigorously.

“Cleotha Abston should and could have been arrested and indicted for the aggravated rape of (the alleged victim) many months earlier, most likely in the year 2021,” the lawsuit says. The AP isn't naming the woman.

Rape kits contain semen, saliva or blood samples taken from a victim. Specimens containing DNA evidence are uploaded to the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, to check for a match.

In Memphis, backlogs have long been a problem. About 12,000 untested rape kits were disclosed there in 2013. A task force was formed, and police began using results to start investigations—and get some convictions.

The city has said the backlog revealed in 2013 has been eliminated. But long delays in testing rape kits persist in Tennessee, including cases from Memphis.

In the Henderson case, Memphis police said a sexual assault report was taken Sept. 21, 2021. A rape kit was submitted two days later to TBI, the bureau said.

“An official CODIS hit was not received until after" Fletcher’s abduction, police said, and probable cause to make an arrest “did not exist until after the CODIS hit had been received.”

TBI said no request was made for expedited analysis and no suspect information was included in the submission.

The kit eventually was pulled from evidence storage and an initial report was completed Aug. 29, the bureau said.

The 2021 DNA matched Henderson's in the national database on Sept. 5, three days after Fletcher's abduction, authorities said. TBI reported the match to Memphis police.

Under Tennessee law, police agencies generally have 30 days to send rape kit evidence to TBI or another lab, but there's no mandate on processing times.

TBI said its budget request was conservative—$10.2 million for 40 scientists and 10 lower-level positions. A West Virginia University forensic calculator said TBI labs needed another 71 positions, the bureau noted.

In DNA testing, the labs currently have six supervisors and 26 special agent/forensic scientist positions, some in hiring or lengthy new hire training. TBI hopes to start the 40 scientists—14 in DNA—by late this month and others by late March.

Still, many have grown impatient at a situation they say called for urgency.

“These are our most vulnerable victims,” said Josh Spickler, executive director of Just City, a Memphis organization pressing for a fairer criminal justice system. “To have a backlog like that build up, and still, to this day, have it be the norm that a rape kit test takes the many months that it does, is really not acceptable.”