ARLINGTON, Tenn. —

83 years ago, a horrific act rocked the town of Arlington.

It was the lynching of a man named Jesse Lee Bond in broad daylight in the town square.

For several generations, his family continues to tell what happened to him, Now, they’re partnering with The Lynching Sites Project of Memphis, or LSP, to put up a historical marker at the site to memorialize Bond and bring awareness to the justice he never received.

“When I walk through the cemetery, tears come down my eyes because I can feel the pain that my family has gone through,” said Ronald Morris, the nephew of Jesse Lee Bond.

Bond is buried in an unmarked grave in Shelby County’s oldest Black cemetery at Gray’s Creek Church outside of Arlington. His family is now working to put a tombstone on his final resting place.

Then 20-year-old Bond was lynched on April 28, 1939, at the SY Wilson store in Arlington.

“Uncle Jesse had to come to the feed store as many sharecroppers did of that time, came and got goods, and then they put it on a ledger,” Morris said. “And then when the crops came in, they came in and paid. But Jesse wanted a receipt. And they didn't like giving out receipts to colored people because they could gyp them and cheat them, so what happened was Jesse demanded a receipt. The young Wilson was there. And eventually he got a receipt. But old man Wilson got angry and said get that person and bring them back into me... When he came back, they began to shoot him and riddled him to the outhouse. They took him, dragged him, castrated him, and stuck him out in the Hatchie river.”

Morris has been working with the LSP to continue putting his uncle’s story in the spotlight. He works closely with John Ashworth, the immediate past president of the Project. Ashworth has helped the organization track the documented lynchings throughout Shelby County.

“We now know about 35 lynchings that occurred,” Ashworth said.

Bond is one of them.

“There are people still around to this day... I mean that was 1939,” Ashworth said. “It's not that long ago.”

But there are still many people who aren’t aware of Bond’s story.

“We know who did it,” Morris said. “They knew who did it. The sheriff knew who did it. Everybody knew who did it. They covered it up. And they say it was an accidental drowning. How can you have an accidental drowning and you got bruises and bullet holes all through your body?”

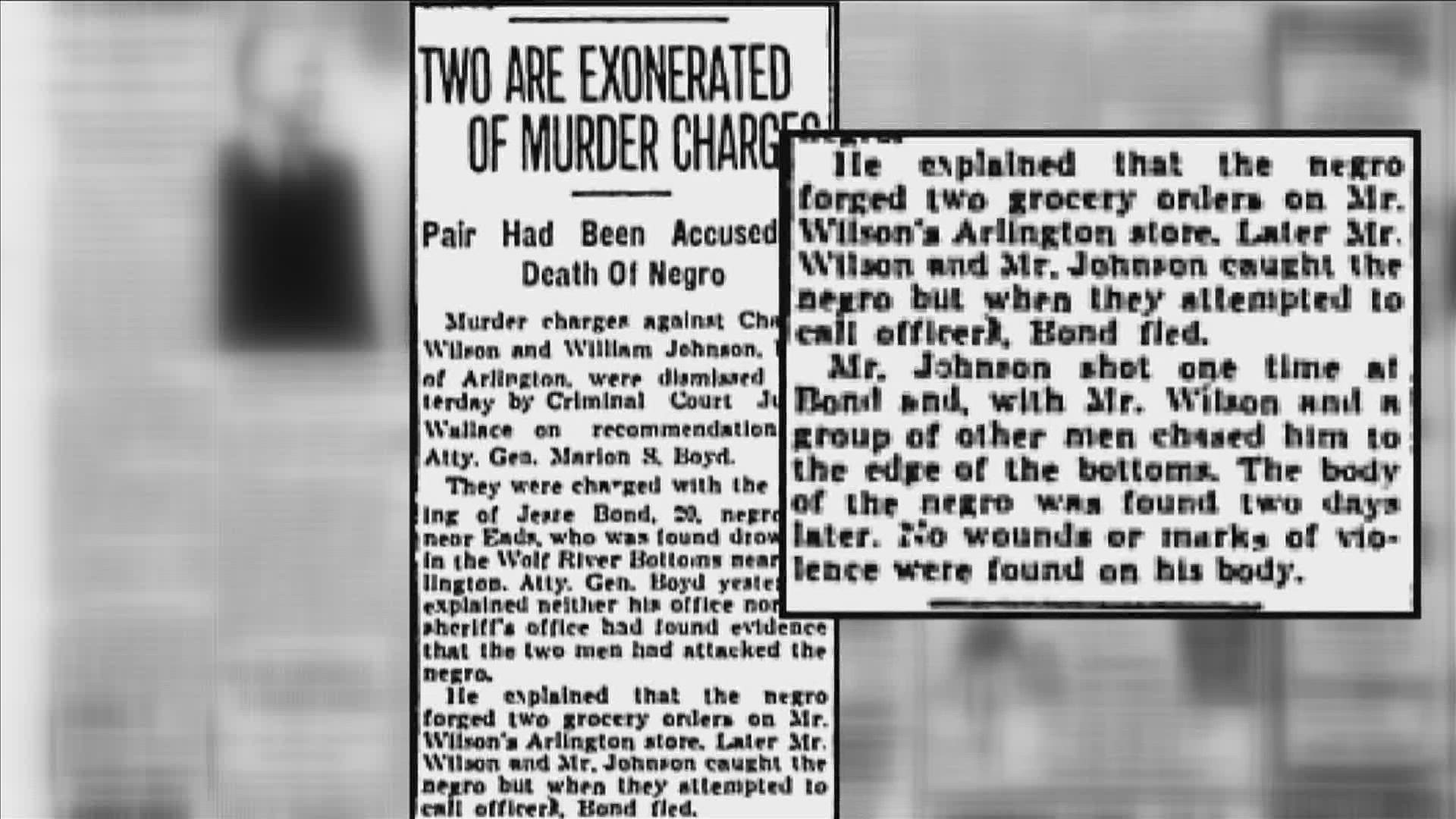

A headline in a small article in a Commercial Appeal paper from January of 1940 reads “Two Men Exonerated of Murder Charges” in regards to the death of Bond.

Those men were Charles Wilson and William Johnson.

The article goes on to say “no wounds of marks of violence were found on his body,” but Bond’s family says that’s simply not true.

“This is an all-white jury and in the 1930s and early 40s,” Morris said. “They weren't gonna convict them.”

While Jesse never got justice, there is some good coming out of sharing his story and others like him.

“We have created a space where people can have honest conversations about the past,” Ashworth said.

Even if that past is painful.

“It robbed me, my brothers, my sisters, my cousins from enjoying one of our uncles... That leaves a scar in your heart,” Morris said.

In March, President Biden signed the first anti-lynching bill in our country to make sure there are no other victims like Bond.

Ashworth said they have been working to put up a historical marker for Bond since 2017 and have hit roadblocks. The city of Arlington said they haven’t received a formal application, and that’s where the process would start for putting up a marker.

The LSP also held a soil collection ceremony from the ground where Bond was killed. That soil will soon be on display at The Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. There’s a memorial dedicated to the more than 4,000 known lynching victims in our country.