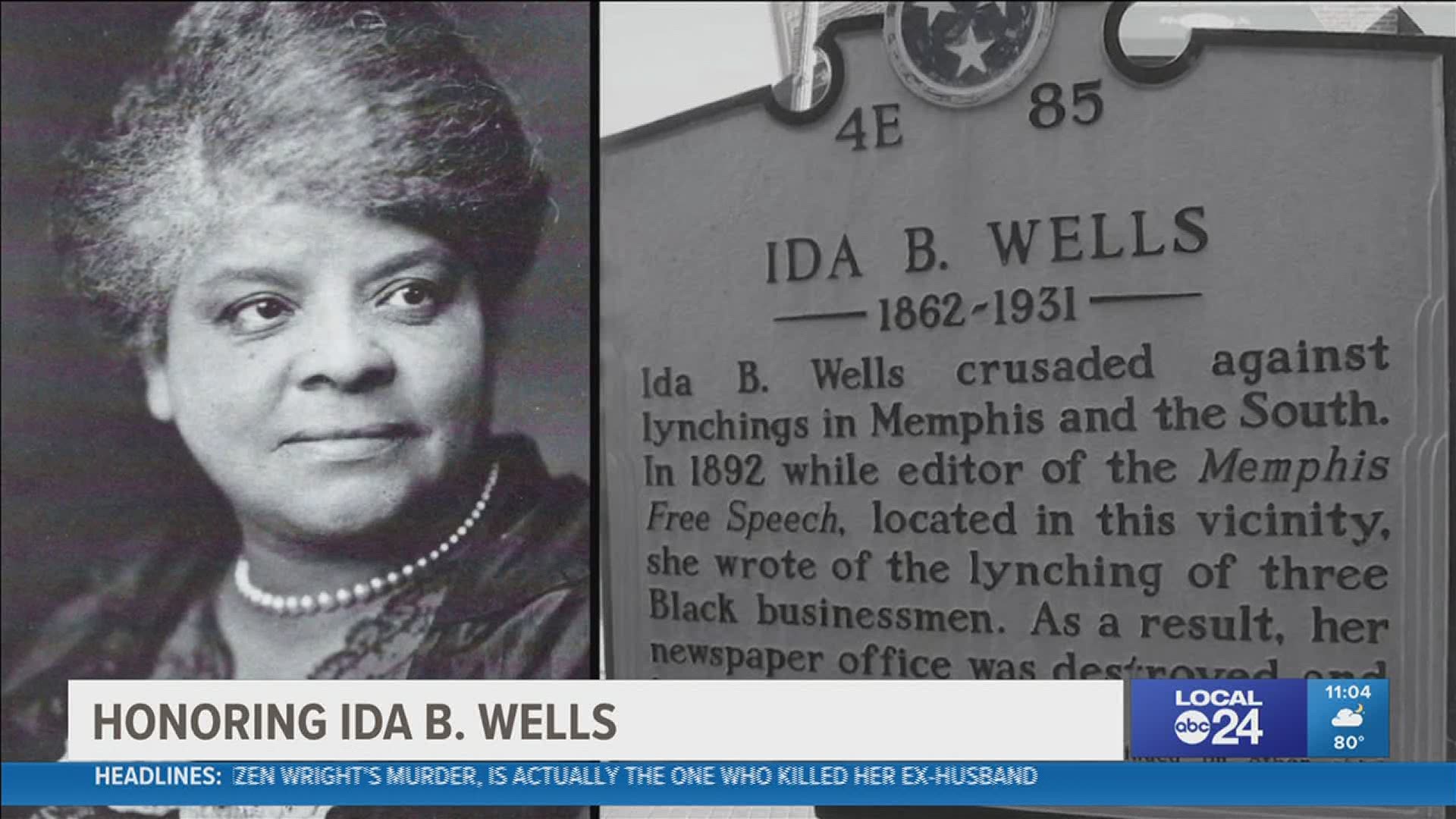

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Ida B. Wells was born into a family of sharecroppers in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on July 16, 1862. Author and professor Rychetta Watkins has researched Wells for publications.

"She came from this family that managed to stay in tact even in the midst of slavery, and her father was politically active," said Watkins.

The deadly yellow fever outbreak of 1878 that swept the Mid-South took the lives of both of Wells' parents and an infant brother and drove Wells, just 16 years old, to Memphis with her siblings. For Wells, family was everything, so she took on a teaching job at a small school house to care for her family. Wells is described as a elegant and striking.

"Even though she was pretty tiny in stature, she carried herself magnificently and part of that was her clothing. From a her earliest ages Wells understood the importance of clothing and appearances and the way that projected about your identity," said Watkins.

It was in Memphis where Wells would begin her pioneering career as one of the first investigative and data driven journalists.

"When she would hear a report of a lynching, she would head out, she'd interview the people in the town and try to figure out how much information she possibly could and she basically put together a database," said Watkins.

That data she collected on lynchings, beginning with the People's Grocery massacre in Memphis, would later be published as The Red Record. Wells began writing during a time when yellow journalism was widely consumed. Her stories of lynchings competed with the propaganda like yellow presses and were shared among the Black population and abolitionists.

"This is how news moved about what was happening, what was coming, what was happening with the Freedman's Bureau, what's happening with the schools that were being developed for the newly freed, formerly enslaved people. In the north, and other places, people were downplaying the severity of the issue, but she went out and collected data and information in order to provide evidence of the extent of the problem in the United States," said Watkins.

Dr. Noelle Trent, Director of Interpretation, Collections & Education at the National Civil Rights Museum said Wells' experience gave her great perspective on the subjects of lynching and civil rights.

"Growing up in this area, she understood that there were these lynchings, these deaths that were happening and when she lost her dear friend in the Peoples Grocery Store massacre she said, 'OK, well why?'" said Trent.

What Wells revealed was Blacks were increasingly accessing their right to vote and organizing. Lynchings were meant to send a signal.

"She came out and said that lynching was a coverup. That people were believing the lie that Black men were sexual predators, and she called it out. She told the truth," said Watkins.

Wells' investigations also exposed how many interracial relationships were consensual, but where punished by white male family members. These writings took courage.

"We forget she's a woman journalist and a Black woman journalist at a time when there aren't that many and this is also a time when investigative journalism as a field or a concept is pretty new," said Trent.

Memphis exiled Wells because of her writings. A memorial steps from where she worked brings her home.