WASHINGTON — The Trump administration on Monday re-designated Cuba as a “state sponsor of terrorism,” in a move that hits the country with new sanctions shortly before President-elect Joe Biden takes office.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced the step, citing in particular Cuba’s continued harboring of U.S. fugitives as well as its support for Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro.

The designation is one of the latest in a series of last-minute moves that the Trump administration is making before Biden takes office on Jan. 20.

Removing Cuba from the blacklist had been one of former President Barack Obama’s main foreign policy achievements as he sought better relations with the communist island, an effort endorsed by Biden as his vice president. Ties had been essentially frozen after Fidel Castro took power in 1959.

As he has with Iran, Trump has sought to reverse many of Obama’s decisions involving Cuba. He has taken a tough line on Havana and rolled back many of the sanctions that the Obama administration had eased or lifted after the restoration of full diplomatic relations in 2015.

Since Trump took office, after a campaign that attacked Obama's moves to normalize relations with Cuba, ties have been increasingly strained.

In addition to attacking Cuba for its support of Maduro, the Trump administration has also suggested that Cuba may have been behind or allowed alleged attacks that left dozens of U.S. diplomats in Havana with brain injuries starting in late 2016.

However, few U.S, allies believe Cuba remains a sponsor of international terrorism, quibbling with either the definition based on the support for Maduro or outright rejecting American claims that Cuban authorities are bankrolling or masterminding international terrorist attacks.

Nonetheless, the Trump administration has pursued an antagonistic policy toward Cuba, steadily increasing restrictions on flights, trade and financial transactions between the U.S. and the island.

The latest sanctions reinstated by the Trump administration include major restrictions that will bar most travel from the U.S. to Cuba and transfer of money between the two countries, a significant source of income for Cubans who have relatives in the United States.

Obama’s removal of Cuba from the “state sponsors of terrorism” list had been a major target of Trump, Pompeo and other Cuba hawks in the current administration. Former national security adviser John Bolton had been a main advocate of restoring the sanctions.

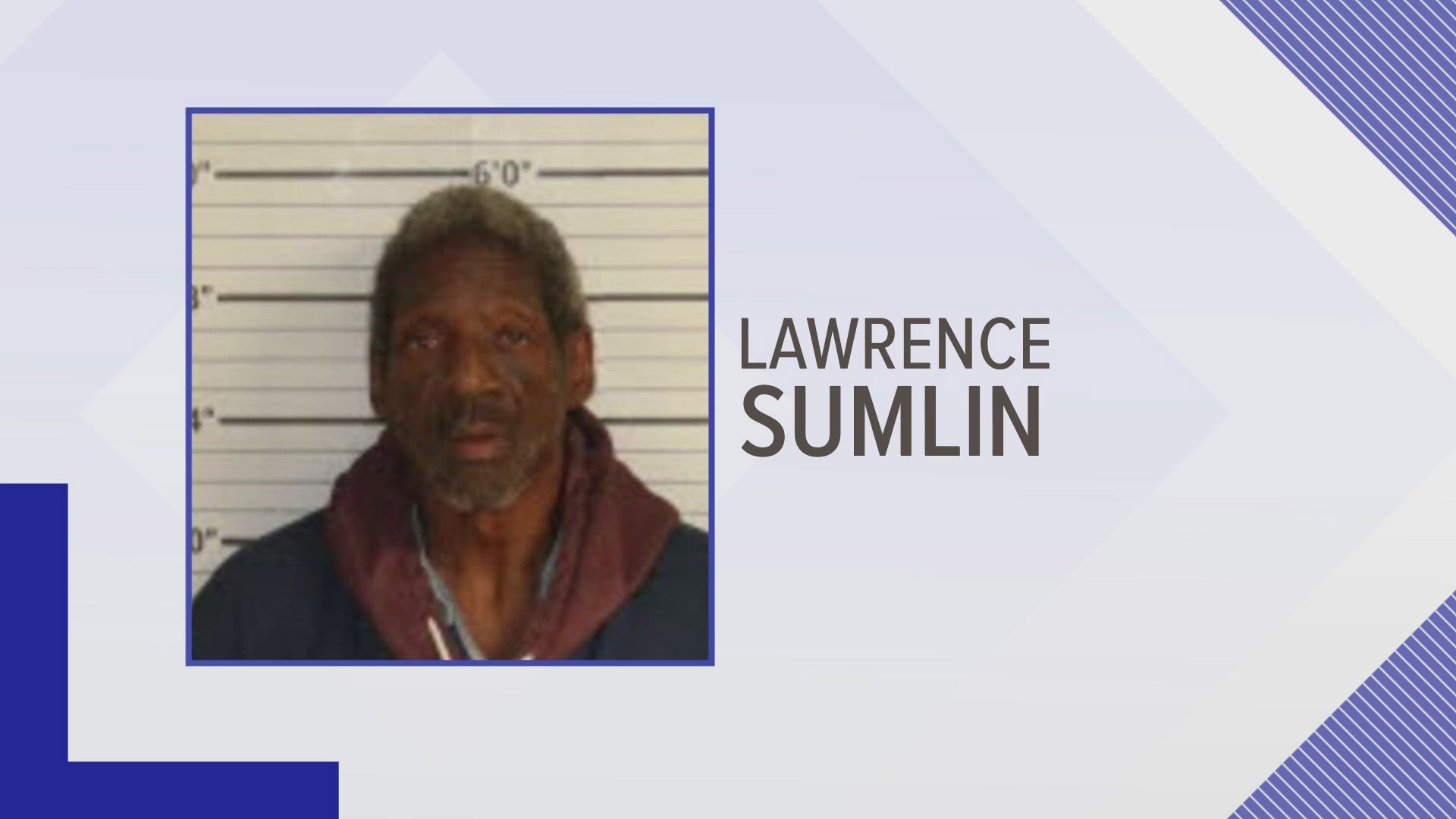

Cuba has repeatedly refused to turn over U.S. fugitives that have been granted asylum, including a black militant convicted of killing a New Jersey state trooper in the 1970s. In addition to political refugee status, U.S. fugitives have received free housing, health care and other benefits thanks to Cuba’s government, which insists the U.S. has no “legal or moral basis” to demand their return.

Cuba has had a long-standing alliance with Maduro, although it has long denied it has 20,000 troops and intelligence agents in Venezuela and says it has not carried out any security operations. Cuban officials, however, have said they have the right to carry out broad military and intelligence cooperation that they deem as legitimate.

The relationship between the two countries has grown strong in the past two decades, with Venezuela sending Cuba oil shipments worth billions of dollars and receiving tens of thousands of employees, including medical workers.

In May 2020, the State Department added Cuba to a list of countries that do not cooperate with U.S. counter-terrorism programs.

In making that determination, the department said several leaders of the Colombian rebel National Liberation Army remained on the island despite attempts at dialogue.

Cuba has rejected such charges. In repudiating the allegations, President Miguel Díaz-Canel has said Cuba was the victim of terrorism. He cited an armed attack on its embassy in Washington last April as one example.

Cubans see the blacklist as helping the U.S. justify the long-standing embargo on the island and other economic sanctions that have crippled its economy.

In the case of the Colombian rebel group, Cuba rejected the extradition of the leaders who were negotiating with Colombian President Iván Duque, whose peace efforts ended in 2019 after a bomb attack by the group in Bogotá.