WASHINGTON — With back-to-school season well underway, there are widespread reports from around the country that a teacher shortage is threatening to leave schools understaffed and overwhelmed.

Major news outlets including MSNBC, Politico, Fox News and countless others have painted a picture of the frustrating situation teachers are facing. "America’s schools are in crisis-mode with a massive teacher shortage" reads one national headline. Another: "The teacher shortage problem is bad. Really bad."

School districts themselves are reporting a lack of teachers. Across north Texas, for example, public records show higher teacher attrition this year than any since at least 2015. In Normandy, Missouri, teachers are being brought out of retirement to fill openings in the school district. Countless similar stories have come out in recent months.

But is there a national teacher shortage?

The answer is complicated and depends on how you look at the problem.

"While the data tells us that, in aggregate, teachers are not leaving the profession at a higher rate than they had before. We also know there are many schools that are struggling to hire right now," said David Rosenberg, a partner at Education Resource Strategies, a nonprofit focused on helping educators and policymakers allocate resources effectively.

"The notion of a national teacher shortage comes down to: it depends on which groups you look at," he said.

Experts interviewed for this story agreed that special education, English-learning and STEM classrooms are among the hardest to hire for. While some teaching jobs have been relatively easy to fill over the years, those positions, especially in lower-income communities, are disproportionately the ones left open.

"There's no doubt that the job of teaching has gotten harder since COVID. What that has done is amplify the issues that have always existed or have existed for a long time with American teaching," Rosenberg said.

The current situation, right after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, is creating a "perfect storm" in many lower-income communities, according to Rosenberg. "All of that is sort of working to make this a particularly challenging moment for many communities."

And teacher shortages are at their core a community-level problem.

"There is no national teacher labor market," said Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the University of Washington. "Teachers are licensed and credentialed by states. So the degree to which there are challenges hiring teachers .... varies a lot from state to state. And it varies a lot depending on what kind of teaching specialty you're trying to hire for."

Goldhaber has studied education data for three decades. He works for both the University of Washington and the nonprofit American Institute of Research. That is to say, he spends much of his time thinking about the big picture of education and how different policies can help students.

"Teacher labor markets, even within states, are pretty localized," Goldhaber said. "Teacher candidates tend to go to school, get their training close to where they grew up. They then tend to do their student teaching close to where they are doing their teacher education. And then they tend to be employed close to both where they did their student teaching and where they did their teacher training."

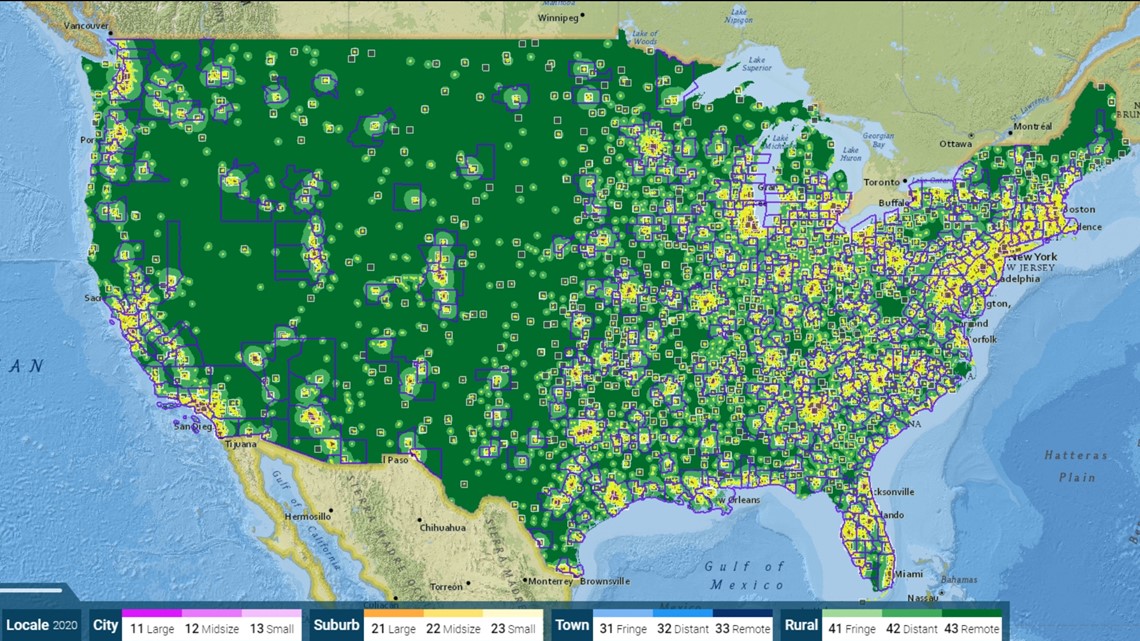

Districts with large staffing holes tend to be rural and remote, or small and underfunded, he said. Those schools tend to be far away from universities and colleges where a teacher can get their degree.

Story continues below map.

Staffing issues among non-teaching staff are also a concern. Clerical and cafeteria workers, bus drivers, classroom aides, and countless other positions outside of the classroom that make schooling possible are also feeling the same pressure, but receive far less attention.

Preliminary data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows about 270,000 fewer school employees in July 2022 than there were in January 2020. While the data isn't broken down by specific job type, it includes teachers, administrators, librarians and other employees who work at schools outside of the classroom.

Rosenberg highlighted counselors as an example, pointing to the increased need for their services in schools: "The mental and physical and emotional health needs of students through the pandemic have been well documented at this point, and we are looking to our schools to be places where we can address those."

"That has led many school districts to try to find more people that, in many systems, in many communities, are hard to find," he said.

Because of post-pandemic hiring — often spurred by extra federal dollars granted as part of a 2021-2022 recovery package passed by Congress — schools aren't only trying to fill existing positions. They're often creating new ones.

Because of the growth in many districts, even schools where teachers aren't leaving or ones that have an easy time filling positions could appear to have openings in their roster, even though they have the same number of teachers from previous years.

"There are more teachers employed in schools now than there were in 2019, despite the fact that...student enrollment in public schools, it has gone down," said Goldhaber. "That's a good indicator that there's a lot of staffing up that's happening to deal with the academic impact of the pandemic."

Federal stats back this up. Historical data and projections from the U.S. Dept. of Education show an estimated 3.1 million public school teachers working in the U.S. Including private schools, that number is around 3.6 million. And that number has remained relatively steady since 2011.

Despite the federal data, it's not an easy pitch to say everything is fine in schools.

"There's nothing I can tell to a school principal or a school or district leader, or a parent whose kids don't have a teacher in their classroom that is qualified and trained up to teach in that classroom," said Rosenberg."

That sentiment rings true in Florida, where the state's largest teachers union estimates there are about 8,000 vacancies, plus another 6,000 open jobs for support staff.

"Both of those numbers are significantly higher than what they were last year," said Andrew Spar, the president of the Florida Education Association, which represents 150,000 teachers.

Spar said the role of coronavirus relief money was minimal in Florida schools, saying he didn't believe federal funds were playing any role in the number of vacancies.

Districts staffing up with new positions, he said, were doing so because of an influx of new students.

Although nationally the number of students enrolled in public schools appears to be relatively steady around 50 million, Spar pointed out that Florida's enrollment numbers had been trending up.

Around 40,000 new students enrolled between the 2020 and 2021 school years. And more will likely come this year.

"Some districts have added more positions because we have more students," he said. "The state of Florida projects 60,000 more students in Florida's public schools. And we don't have enough teachers and staff right now to handle all of the students in our schools."

The enrollment of college students in teaching programs has been on the decline in Florida over the past 12 years, he said.

"In 2010, there were 8,000 graduates from Florida's colleges and universities of new teachers. This summer, it was estimated to be between two and three thousand," Spar said.

One of the issues driving teachers away is the politicization of education, he contends.

Education has become a flashpoint for both Democrats and Republicans, who regularly spar in Congress and on cable news over everything from COVID-19 guidelines to curriculum standards.

"We should not allow anyone to infuse their political ideologies into our public schools, for .... political purpose," Spar said, citing initiatives from Florida Gov. Ron Desantis that he said would lower the standards for teachers, harming both the profession's credibility and the education of students.

The initiatives include a new law that would allow some veterans to teach in classrooms without a degree.

"The idea of saying you don't need a degree, you don't need any education background, it's crazy," Spar said.

But drawing more teachers into the profession despite the well-known hardships that go with the job is difficult. A growing coalition of voices are calling for a reimagining of the way teachers are paid.

In comments to CBS, U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona denounced low teaching wages.

"The fact that we've normalized teachers driving Uber on the weekends to make ends meet or working at a restaurant waiting tables to make ends meet. We have to lift the profession," he said.

Cardona said the pay issue was an important one to show teachers that they're respected for the work they do.

"This teacher shortage issue is a symptom of what I call a teacher respect issue. We need to respect the profession better," he said. "College graduates earn 33% more than your average teacher when they leave."

But even changing how teachers are paid comes with its own complications. Unlike most jobs in the private sector, where factors such as the employer's need for a particular skillset influence salary, public schools often pay teachers solely based on years of experience.

"Ultimately, the most sensible, straightforward solution is to change compensation," said Goldhaber. "That's generally not super popular. Teacher's unions tend to like the salary to be really uniform, except [when] it varies by your degree and experience level. There's resistance to differentiating based on location or subject specialization."

Spar's union, the Florida Education Association, says teachers they represent make an average of $51,000 per year.

He defended the experience-based compensation system they use when bargaining with school districts.

"It does take time to really hone that craft," he said. "In just about every industry, including in education, you get better the more you do it."

Spar said that legislatively-mandated hikes to beginning teacher pay in Florida have come at the expense of more experienced teachers.

"We have taken money from experienced teachers and moved it forward on the pay scale so that brand new teachers are making a more competitive salary, which is great," Spar said. "But we did it by taking from the experienced teachers. What we have to do is increase the pay of all in a fair and equitable way."