‘Nobody talks about it’: Understanding the rise in youth suicide

VERIFY spoke with mental health experts and parents to get a better understanding of the many factors that contributed to the rise in youth suicide in the U.S.

Editor’s note: This story includes references to suicide and suicidal feelings.

June 15, 2016, was the last day of school for students in Stafford County, Virginia. Tara Lowery, a mother of two, was organizing the classroom where she was a teacher’s assistant. Because it was an early release day for students, Tara asked her 16-year-old son Jake if he could pick up his little brother, 10-year-old Jesse, from school.

“Jake was a little angry that day because he had to sit in the office. I called a little while later…gave them time to get home. I called and asked, ‘Are you okay?’ He said, ‘Yeah. I’m fine, now.’ ‘Okay, as long as everything is okay.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I’m heating up some macaroni and cheese,’” Lowery said.

Knowing that both of her sons were safe at home, Lowery continued to organize her classroom.

“All of a sudden, the phone rang. It was Jesse, and he’s screaming in the phone. I said, ‘You’ve got to calm down. I cannot understand a word you’re saying. Take a breath.’ So, then he told me. He was hysterical. So, I was like, hang up and call 911. He did. And he followed their directions completely,” Lowery said.

“Apparently, I threw my phone at one of my coworkers and told her to call my husband. I couldn’t even find his phone number or name in my phone. She’s like, ‘What do I tell him?’ ‘Tell him Jake killed himself.’ All I could do was scream. That’s all we could do. It was horrible. It was the worst day of my entire life,” Lowery said.

Brad Hunstable, a husband, father, and the CEO of an electric motor design company in Fort Worth, Texas, also lost a child to suicide on April 17, 2020.

“It’s hard to explain. It was a beautiful sunny day, but there was a storm all around me, and I wish it on nobody,” Hunstable said. “We were in the middle of the pandemic. The height and start of it. We weren’t letting our kids go outside. They had shut and locked down schools.”

“I remember my wife and girls making fun of me about something, I can’t remember what it was, but I remember Hayden walked up to me and said, ‘I love you, Dad,’” Hunstable said.

“I kissed him on the head, and I still remember to this day the feeling of his hair on my lips. I hugged him. It was a hard hug. I went to my office downstairs and took a phone call. My little daughter, who was 8 at the time, came downstairs and said Hayden [killed] himself. I ran upstairs and tried everything I knew,” Hunstable said.

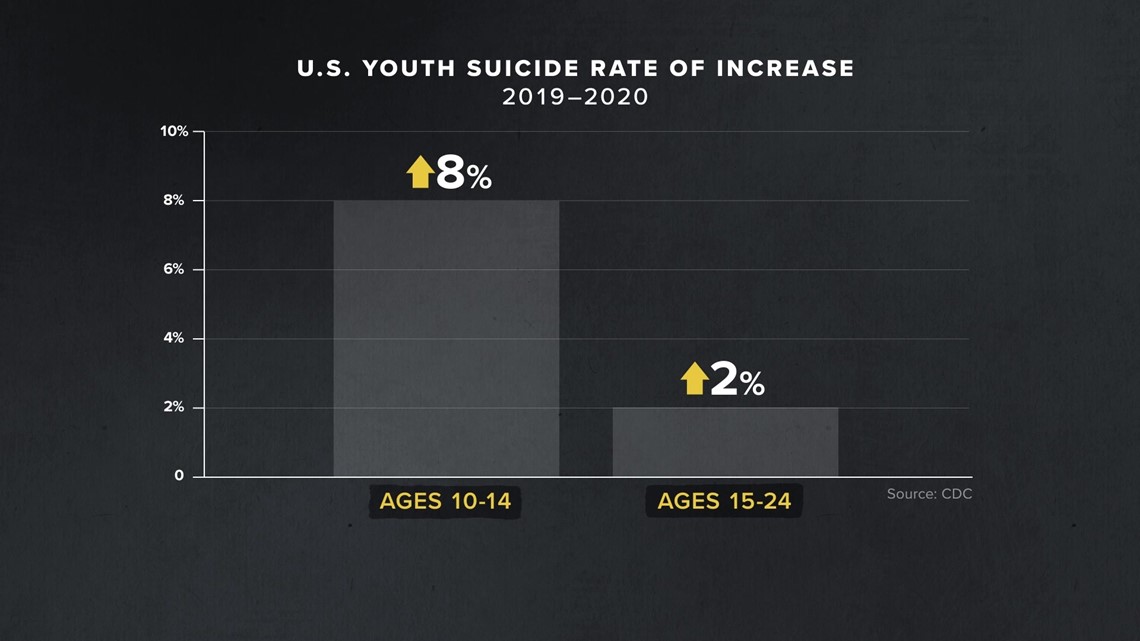

In 2020, there were more than 6,600 deaths by suicide among youth ages 10 to 24, according to a report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The youngest group, ages 10 to 14, saw an increase of 8% from 2019 to 2020, while those aged 15 to 24 saw a 2% increase.

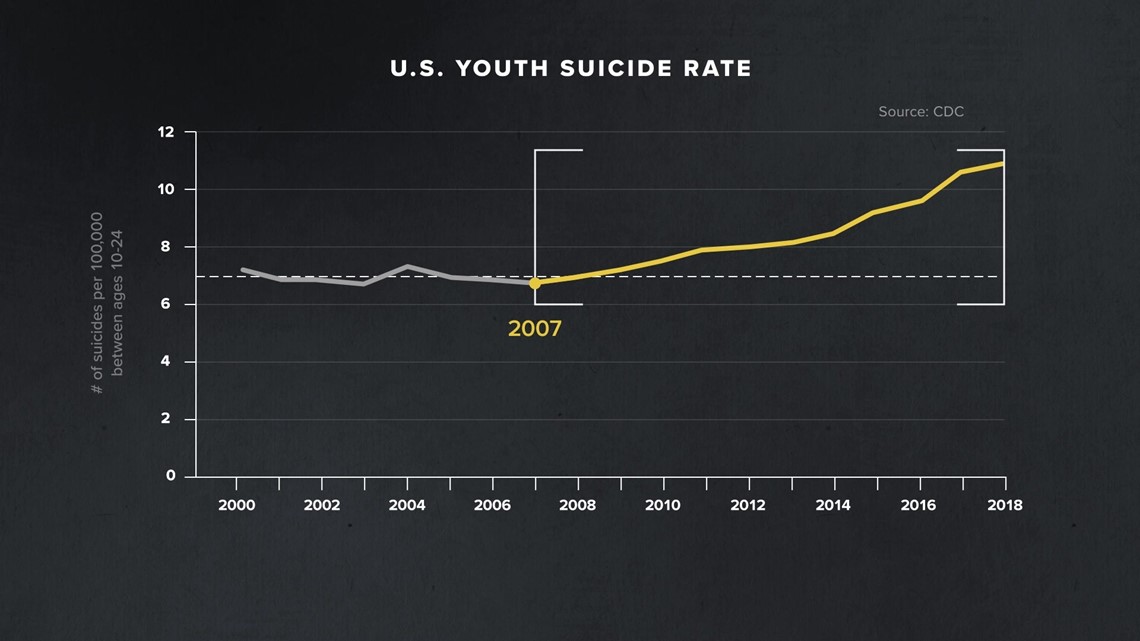

While the youth suicide rate in the U.S. did increase in 2020, the pandemic did not mark the start of a new trend. In fact, a National Vital Statistics report from 2020 shows those rates have been on the rise for more than a decade, which Benjamin Shain, M.D., Ph.D., who serves as the head of child and adolescent psychiatry at NorthShore University HealthSystem, can attest to.

“Mental health in youth has been deteriorating for a while. Definitely, before COVID….for probably for the last 10 years, with an increase in kids seeking services for common things like depression or anxiety, an increase in suicide attempts, and suicides. And this is true, again, even before the pandemic,” Shain told VERIFY.

From 2000 to 2007, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) said the youth suicide rate in the U.S. stayed around a rate of 7 per 100,000 children. However, 2007 marked the beginning of a dramatic shift, according to a 2020 report published by the CDC’s National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), which tracked suicide rates among Americans aged 10 to 24 from 2000 to 2018.

The youth suicide rate increased by 57% — from 6.8 per 100,000 in 2007 to 10.7 in 2018. In 2019, the CDC ranked suicide as the second leading cause of death among youth, after accidental injuries.

To get a better understanding of the many factors that have contributed to the rise in youth suicides in the U.S., the VERIFY team analyzed scientific studies and spoke with child psychiatrists, parents, and counselors. Together they address the rising rate of mental health disorders in youth, the impact of social media, the decreased access to mental health services, and the need for more conversations about the risk factors and warning signs of youth suicide.

THE SOURCES

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS)

- National Vital Statistics System (NVSS)

- U.S. Surgeon General’s youth mental health report

- American Psychological Association

- National Association of School Psychologists

- Common Sense Media youth media use report

- Study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychological Science

- Meta report on teen well-being and Instagram

- Study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Bart Andrews, Ph.D., chief clinical officer at Behavioral Health Response

- Roger McIntyre, M.D., professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto and head of the Scientific Advisory Board for the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance

- Benjamin Shain, M.D. Ph.D., head of child and adolescent psychiatry at NorthShore University HealthSystem

- Nancy Turner, Ed.D., director of mental health at Rock Hill Schools

- Brad Hunstable, father of Hayden Hunstable

- Tara Lowery, mother of Jake Lowery

Chapter 1 Risk Factors

“Suicide is not a mental illness. But most people, more than 80% of people who die by suicide, have a mental illness — and depression is the most common mental disorder associated with suicide,” Roger McIntyre, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Toronto, told VERIFY.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says mental health disorders among children “continue to be a substantial public health concern.” From 2013 to 2019, the public health agency collected mental health reports on youth in the United States between the ages of 6 months and 19 years old. Its data show that anxiety and depression are two of the most common mental health disorders in that age group, along with ADHD and behavior problems.

Of children and adolescents between the ages of 3 to 17 years old, researchers found that one in 11, or 5.8 million youth, were diagnosed with anxiety. And among those aged 12 to 17 years old, 20.9% had experienced a major depressive episode at some point in their life, according to the CDC.

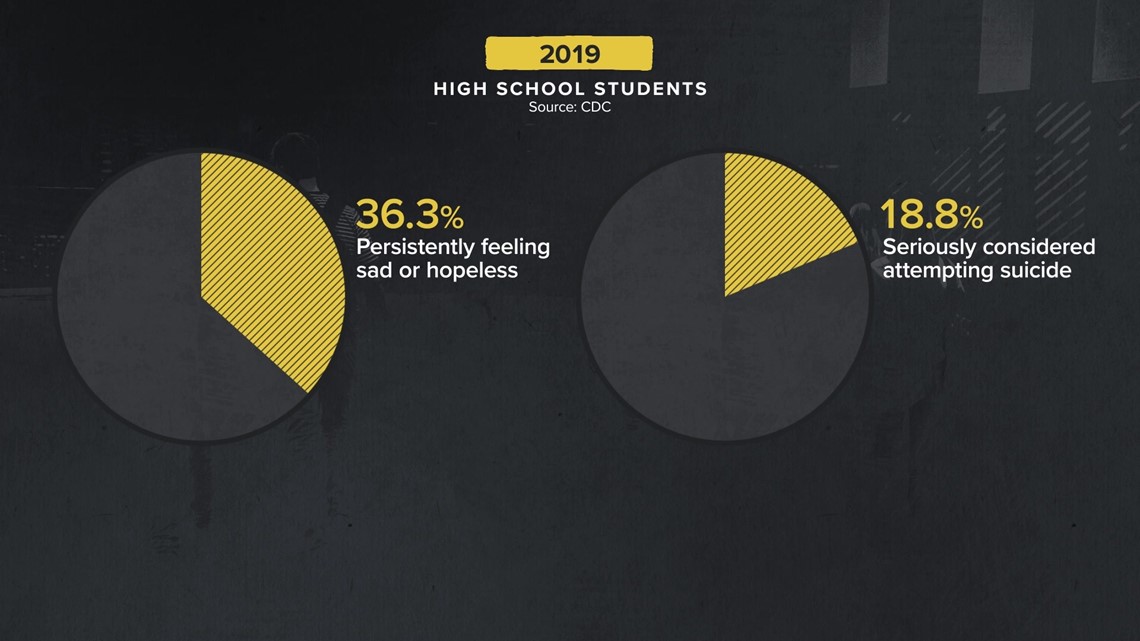

In 2019, CDC researchers found more than 36.3% of high school students reported persistently feeling sad or hopeless in the past year, and nearly 20% had seriously considered attempting suicide.

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, previously known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, a U.S.-based suicide prevention network, lists risk factors for suicide on its website. Some of the risk factors include:

- Mental health disorders, particularly mood disorders, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and certain personality disorders

- Lack of healthcare, especially mental health and substance abuse treatment

- History of trauma or abuse

- Loss of relationship(s)

- Lack of social support and sense of isolation

“We have to remember something: Suicide is never caused by a single event. No one has ever died by suicide because of one reason,” McIntyre said. “Research into suicide has revealed dozens, in fact, in some studies, over 100 risk factors for suicide.”

While these risk factors are characteristics that make it more likely that someone will consider, attempt, or die by suicide, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline says they “can't cause or predict a suicide attempt.”

Experts VERIFY spoke to say spotting these risk factors has fallen on a shrinking number of mental health professionals over the years as access to services has been decreasing.

Chapter 2 Lack of access to mental health services

“There's been a drastic increase in kids seeking [mental health] services in general,” Ben Shain, M.D., Ph.D., the head of child and adolescent psychiatry at NorthShore University HealthSystem, told VERIFY.

Before the coronavirus pandemic began in March 2020, the CDC found that 1 in 5 teens aged 13 to 17 had a mental, emotional, or behavioral disorder, such as anxiety, depression, or ADHD. The public health agency also found that only about 20% of teens with a disorder in this age group received care from a mental health provider.

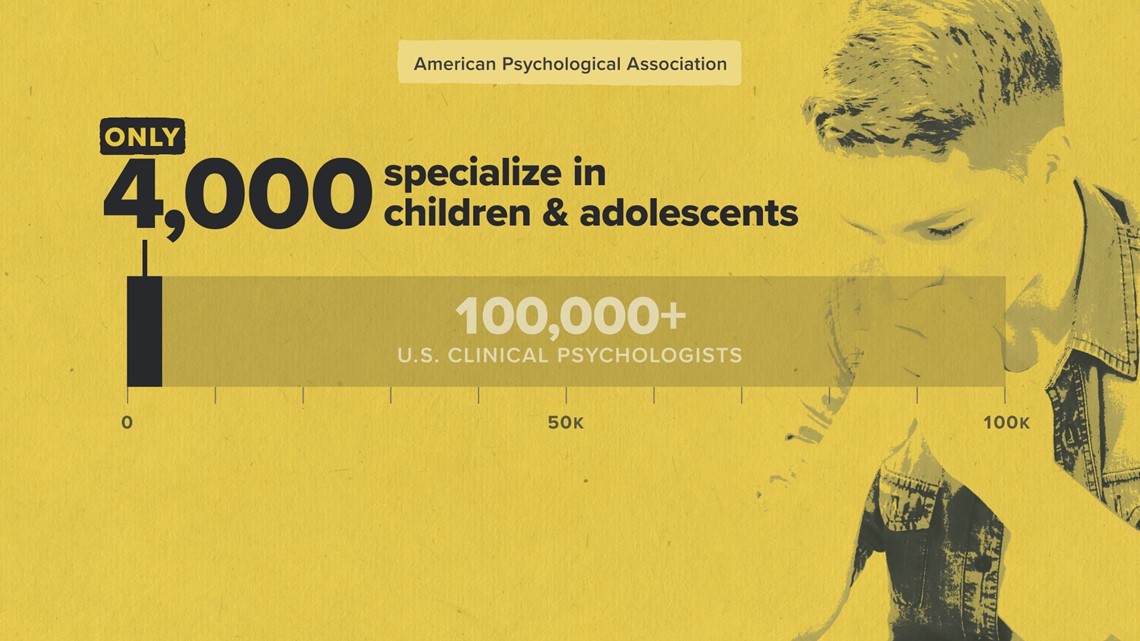

According to 2019 data from the American Psychological Association (APA), only 4,000 out of more than 100,000 U.S. clinical psychologists are child and adolescent clinicians.

“In my area, there's kind of nothing available. There are way too many clients compared to the number of providers, and that's true for therapists, for psychiatrists, for inpatient hospital beds, for day programs….it's mostly not available, you know, given the demand,” said Shain, who is based in Deerfield, Illinois.

School psychologists are also in short supply, according to the APA, leaving children without enough support in the classroom.

The National Association of School Psychologists, which calls the shortage of school psychologists a “critical policy issue” on its website, recommends a ratio of one school psychologist per 500 students in public schools — but in 2019, their data showed that number was actually closer to one school psychologist per 1,200 students.

Chapter 3 The impact of social media and screen time

“My son died from the coronavirus — but not in the way you think. Human condition is not to be socially isolated. I heard someone say it’s like summer for these kids. It’s not like summer for these kids. It’s just not. You’ve got kids who have no interaction with their friends other than Fortnite and FaceTime. That’s not like summer,” Brad Hunstable said in a video he shared online after his son Hayden’s death.

At the start of the pandemic, many schools stopped in-person learning, children were stuck at home, and hanging out with friends was discouraged. Experts say the pressures on youth mental health continued to increase while access to mental health services became even more strained as children reported feeling more isolated.

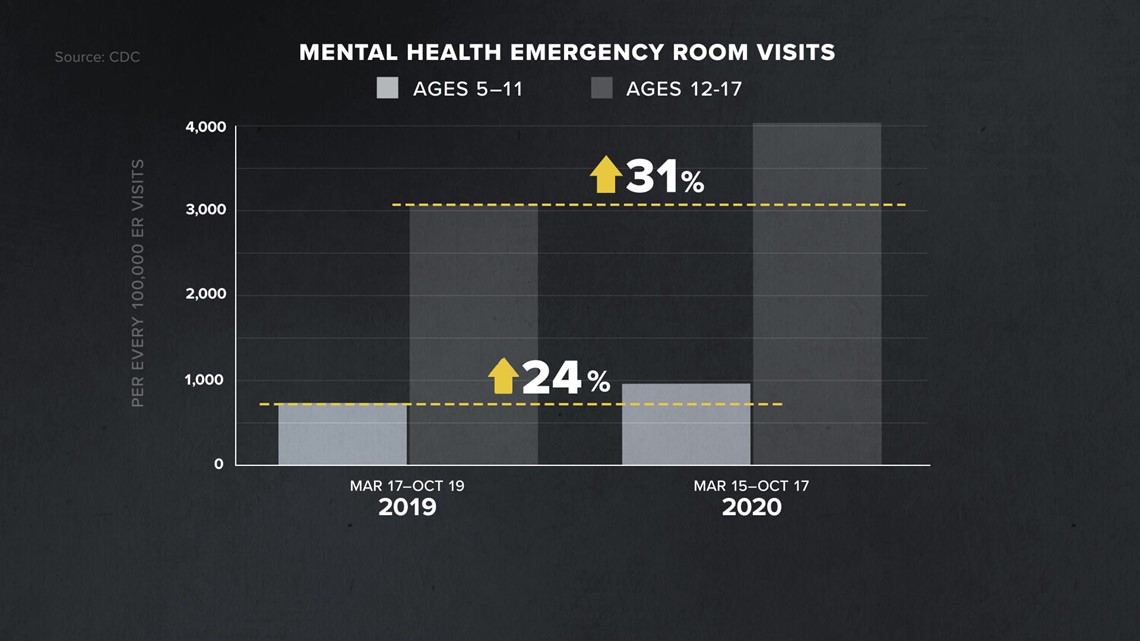

According to CDC data from mid-March to mid-October 2020, there was a 24% increase in emergency room visits for mental health reasons for children ages 5 through 11, and more than a 30% increase in visits for those between 12 and 17 years old, when compared to 2019.

Missing the normal outlets for face-to-face socialization that in-person school provides, more young people turned to social media for that interaction during the pandemic.

Many experts believe that social media can be harmful to youth mental health and that increased time on smartphone applications can lead to exacerbating risk factors for suicide, including lack of sleep, increased anxiety and depression, and feeling isolated.

“I do wonder about the dislocation that we’ve seen in young people, especially those between 12 to 19 for example, not being in school. In some cases, I’m hearing children have not been in school for a year and a half. That’s beyond a measure in terms of the impact that has on someone’s sense of social connectedness,” McIntyre said.

“Of course, as you know, many people can just hop on Instagram or Facebook or Twitter, but that gets complicated as well because we know that there is a complex relationship between social media utilization and well-being,” McIntyre continued.

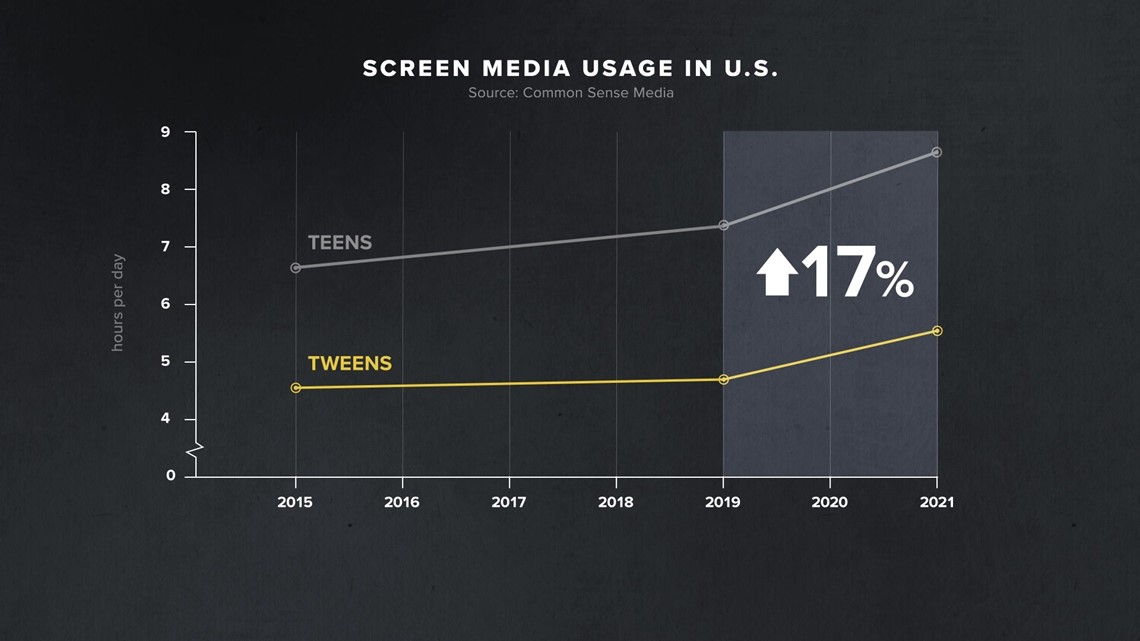

A 2021 survey published by the nonprofit consumer advocacy group Common Sense Media showed that overall screen use among tweens and teens increased by 17% from 2019 to 2021. The number grew more rapidly in those two years than it had in the four years prior.

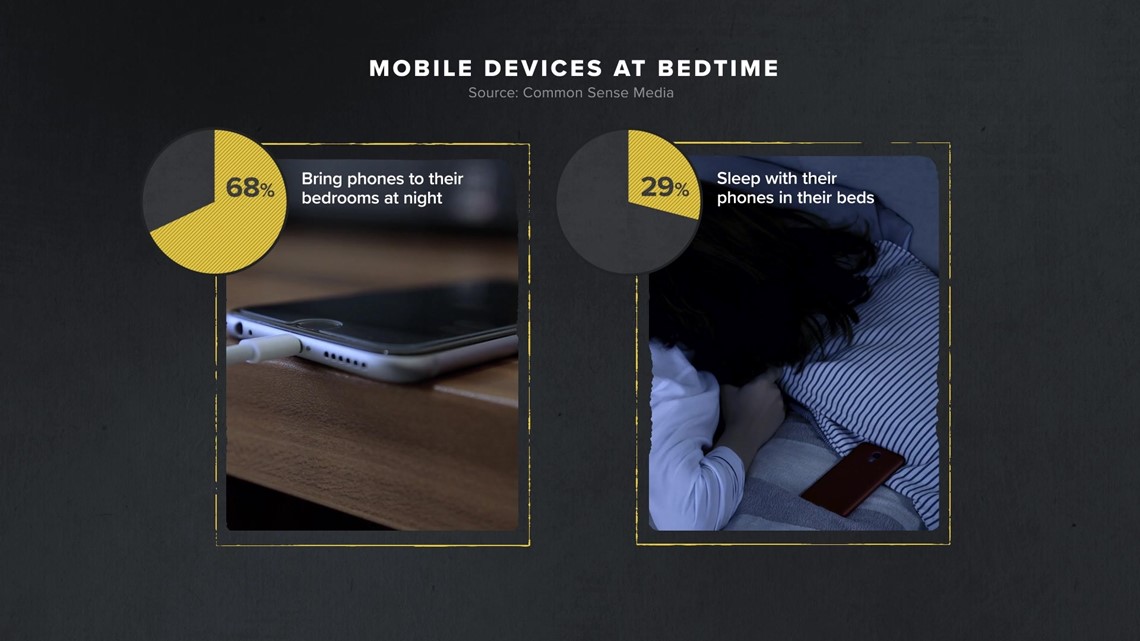

Common Sense Media also found that two out of three teenagers with mobile devices keep them in their rooms overnight, and nearly a third bring them into their beds while sleeping. According to the Sleep Foundation, screen time late into the evening can cause disrupted and fragmented sleep. Lack of sleep, or oversleeping, is one of the risk factors for suicide.

“These kids live for socialization. They judge themselves 80% based on how their peers judge them. And so, now they're in a place where they can get feedback — could be good feedback but it also could be very bad feedback on a 24/7 basis. So they can't turn off. They can't relax. They are potentially constantly in touch on social media and electronically with other applications,” Shain told VERIFY.

Instagram, a photo and video-sharing social media network owned by Meta, is used by millions of young people on a daily basis. In 2019, Common Sense Media asked young people on social media to rank the apps they wouldn’t want to live without, and Instagram was tied for third place with 13% of the vote, behind YouTube and Snapchat.

Researchers inside Instagram have been studying how the photo-sharing app affects its young users. Internal research presented by Instagram in March 2020 found the app was harmful to many young people, causing increased feelings of “anxiety and depression.” Among teens who reported suicidal thoughts, 6% of American users traced the desire to kill themselves to Instagram, according to the company’s internal data. Instagram said it is taking steps to improve the platform in order to address these issues.

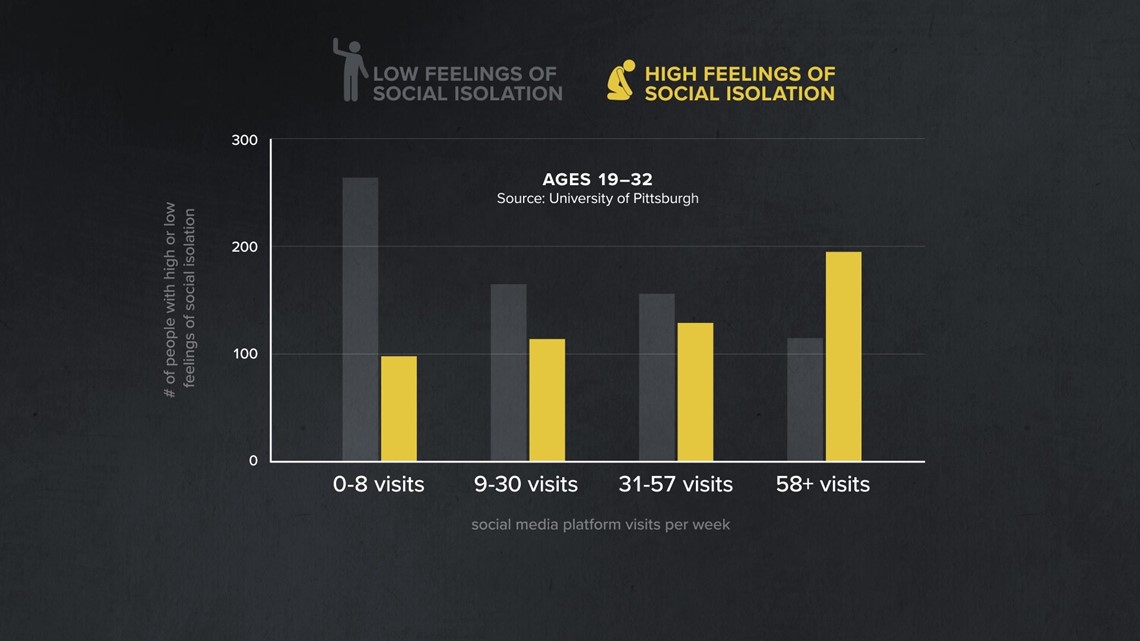

Some researchers have found that social media use can also have an effect on feelings of social isolation in children and young adults. A 2017 study of 1,787 U.S. adults age 19 to 32 years old found that young adults with high social media usage reported feeling more socially isolated than those who are not on social media as often.

Jean Twenge, Ph.D., a psychology professor at San Diego State University, assessed the relationship between social media use, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and social isolation in adolescents in grades eight to 12 in a 2017 study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychological Science. Twenge found that social isolation is one of the major risk factors associated with suicidal outcomes.

"We found that teens who spent five or more hours a day online were 71% more likely than those who spent less than an hour a day to have at least one suicide risk factor,” Twenge said in a blog post about her research. “Overall, suicide risk factors rose significantly after two or more hours a day of time online.”

Chapter 4 "Nobody wants to talk about it"

“I truly believe that when we have more awareness, when we're talking more about it, we have less stigma,” Nancy Turner, Ed.D., told VERIFY.

Turner serves as the director of mental health at Rock Hill Schools in Rock Hill, South Carolina. She said there is no set age for when a child starts to understand what suicide means, but throughout her over 20 years of working with children, she says they are getting younger and younger.

“There has definitely been an increase in mental health issues, as well as suicidal ideation and issues along that line. It is very concerning,” Turner said. “And through the years, we have seen a rise in this area, as well as across the board with significant mental health concerns.”

A 2020 study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry found that children with depression between the ages of 3 and 6 years old had an idea of what suicide was and had an advanced understanding of death compared to their nondepressed peers.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Surgeon General's report on youth mental health also showed from 2009 to 2019, the proportion of high school students reporting persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness increased by 40%, those seriously considering attempting suicide increased by 36%, and the number of students who created a suicide plan increased by 44%.

Although recognizing suicidal ideation in children can be challenging, Turner says there are warning signs people can look for.

“First and foremost, listen to your child. Ask direct questions — as early as 9 or 10. It seems so young, however, before hearing signs and seeing signs of depression, or seeing signs of students feeling alone, or they may feel rejected. Parents notice this, they might think, ‘Well, they're going through something.’ Don't wait. Be direct. Ask questions,” Turner said.

Turner notes that there are other small warning signs that might be missed, including changes in eating or sleeping patterns, giving away belongings, losing interest in their favorite pastimes and after-school activities, as well as sudden withdrawal.

“Ask that direct question. Are you thinking of hurting yourself? Are you thinking of killing yourself?” Turner said.

Tara Lowery and Brad Hunstable hope their stories inspire others to have more conversations about youth mental health and suicide.

“I do think talking about mental health in school has traditionally been taboo. I get it, people, that's a scary topic. I mean, suicide, depression, and anxiety are very scary topics, and we don't know what we don't know. We tend to pull back, and unfortunately, that's the wrong thing to do,” Hunstable told VERIFY.

“My big thing is, it's got to get out into the schools and out into the public. Everybody thinks it's the elephant in the room and nobody wants to talk about it,” Lowery said. “It's right in our faces. I am done with this. I'm done with people hiding it. It's got to get out there.”

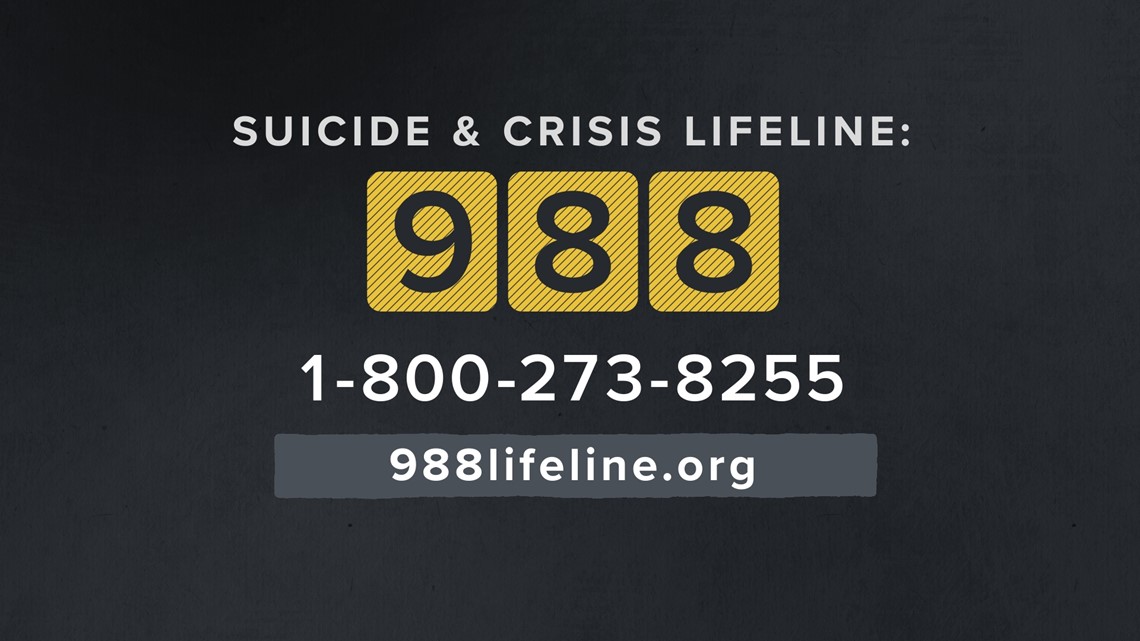

If you or someone you know is in a crisis or having thoughts of suicide, call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988. The lifeline can also be reached at its former number 1-800-273-8255 or online at 988lifeline.org. You can also text HELLO to 741741 to reach the Crisis Text Line. A comprehensive list of suicide prevention resources can be found on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services (SAMHSA) website.

Credits:

- Ariane Datil, VERIFY Host

- Erin Jones, Digital Journalist

- Alanna Delfino, Photojournalist and Video Editor

- Tamika Cody, Producer/Editor

- Mauricio Chamberlain, Researcher

- Amie Casaldi, Creative Lead/Sr. Motion Designer

- Eleni Hosack, Producer/Editor, Graphics

- Erica Jones, Deputy Editor

- Sara Roth, Senior Editor, Digital

- Lindsay Claiborn, Senior Editor, Video

More from VERIFY: No, the US suicide rate did not increase in 2020 during the pandemic