Who were the Memphis Red Sox? | Remembering the history of Memphis' Negro League baseball team

Despite being known for basketball, Memphis has a storied history in baseball. Included in that history are the Memphis Red Sox, a Black, family-owned team.

Many of us Memphians have enjoyed a day at AutoZone Park. Whether we grew up going to see future major leaguers or just went for some peanuts and Cracker Jacks, Redbirds baseball has been a staple of downtown for decades. Memphis isn’t nationally renowned for its baseball, but for over a century, the city has played host to multiple professional baseball teams.

One of the most historically significant is the Memphis Red Sox. The Red Sox were Memphis' Black-owned Negro League baseball team.

The Early Days

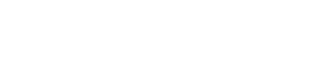

In 1922, when baseball—and much of the country—was segregated, the Memphis Red Sox combined the rosters of two established Black teams—the A.P. Martin’s Barber College Boys and the Memphis Union Giants.

A.P. Martin’s Barber College Boys, commonly known as the Barber Boys, played in Russwood Park, the home of the white minor league Memphis Chicks in the heart of what is now the medical district.

When the two rosters combined to become the Memphis Red Sox, they would also change ownership. Moses and Miller Dandridge, co-owners of Liberty Auto Repair of Memphis, bought the team.

However, in the same year, the two brothers sold the team to Richard Stevenson Lewis, the founder of R.S. Lewis Funeral Home. Memphians today might know Lewis as the man who prepared Martin Luther King Jr.’s body for his funeral or maybe just recognize the name from his funeral home business, R.S. Lewis and Sons, which still operates today.

In his time as owner of the ballclub, Lewis helped the Red Sox achieve something few other Negro League teams had—owning the ballpark where they played.

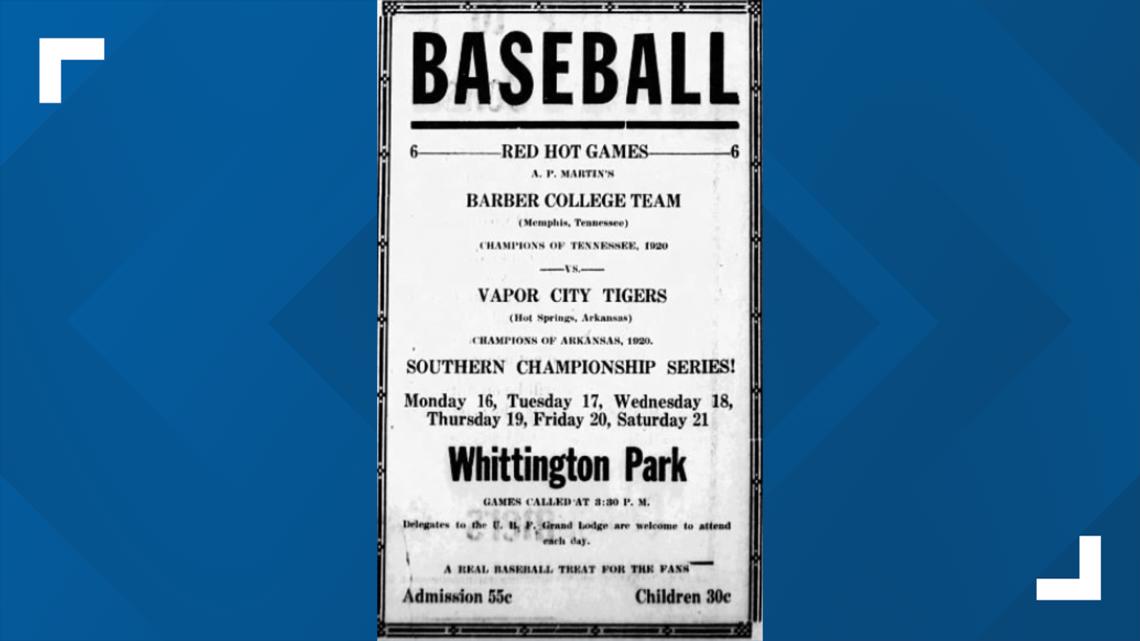

In 1923, Lewis opened the eponymous Lewis Park as the home of the Memphis Red Sox, eliminating scheduling and monetary obligations that came with leasing a white-owned stadium as a Negro League team. The ballpark was located on what is now East E.H. Crump Blvd and, on top of the ballgames, hosted events for the Black community. A stadium owned by a Black man that was used for Black-run events was an unprecedented feat.

The Martin Brothers

In 1929, as collateral for a loan, Lewis sold the Red Sox to Dr. J.B. Martin, a Memphis pharmacist, dentist, real estate mogul and Republican political leader. Martin was also a Black man and made the ballclub a family affair, sharing ownership with his brothers, B.B. and W.S. Following the trend of Lewis before him, the ballpark was renamed Martin Stadium.

Eight years later, the Red Sox would win their first and only pennant—though under strange circumstances. In a Negro American League championship series against the Atlanta Black Crackers, the Red Sox won two games at home.

Atlanta and Memphis would not meet again in the postseason due to multiple scheduling conflicts with the Black Crackers. Months later, since Memphis won the only games played, the league declared the Red Sox champions!

In 1940, police were stationed outside of J.B. Martin's South Memphis drug store. Police alleged Martin was selling illegal narcotics out of his store; a rumor that was never found to have any merit. Police would drive away business by harassing customers attempting to enter the store.

Earlier that year, Martin had voiced his support for Wendell Willkie, who opposed President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Many historians allege E.H. "Boss" Crump, a prominent and very influential democrat who endorsed the third-term incumbent President Roosevelt, had a hand in the harassment.

In Memphis, Black residents were always allowed to vote, and Crump's political machine relied heavily on Black votes. Martin was influential in the Black community, and historians believe that is why Crump drove him out of town. After months of harassment and threats of prosecution, Martin left for Chicago, transferring ownership of the team to his two brothers, B.B. and W.S.

J.B. Martin would go on to own one of the most famous Negro League teams, the Chicago American Giants, and serve as president of the Negro American League.

Crossing the Color Barrier

Throughout the team's playing history—the story of the Memphis Red Sox is one of gradual decline in on-field success. Some of the factors contributing to that decline were out of the team's hands.

For one, many players from the Negro Leagues were drafted or enlisted when the U.S. entered World War II. Even those who stayed had to make sacrifices to support the war effort. Rations on gasoline and tires meant less road trips for ballclubs nationwide. All these factors hit the Negro Leagues particularly hard; many teams were already struggling before war.

In years after the war, the Red Sox and other Negro League teams faced another contributing factor to their eventual end: integration. Progress was finally being made in professional sports, and Black players were making waves on major league rosters.

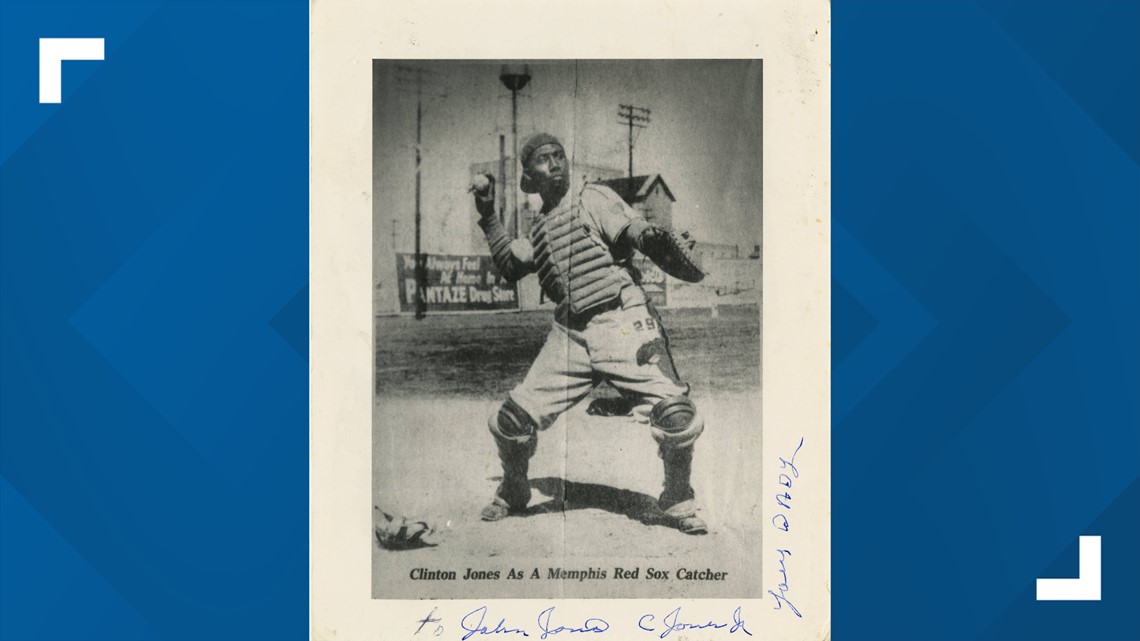

Jackie Robinson is the most well-known player for breaking the baseball color barrier in 1947, but the Memphis Red Sox had plenty of pioneers that made the same journey and faced the same adversity. The same year Robinson made history, Dan Bankhead, a Memphis Red Sox pitcher, became the first Black man to pitch in a major league baseball game after the team sold his contract to the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Marshall “Sheriff” Bridges is another Red Sox pitcher that would go on to play in the majors. Bridges played for the St. Louis Cardinals, Cincinnati Reds and even the New York Yankees, with whom he would pitch in game 4 of the 1962 World Series.

Integration deeply impacted the Negro Leagues. With major league scouts snatching big names from rosters, spectators were no longer going to see the best Black ballplayers in Negro League games—they were looking to the majors. This hit close to home when in 1950, the Chicago White Sox bought the contract of Red Sox first baseman, Bob Boyd, for $12,000.

B.B. Martin, a part owner at the time, authorized the deal, but W.S., his brother and the controlling owner and president of the ballclub, did not sign off on the deal. W.S. Martin went on to sue the White Sox for $35,000 in damages, claiming they enticed Boyd to leave. Eventually, after meeting with his brother, J.B., the lawsuit was settled, but no payment to W.S. Martin was ever documented.

In 1958, W.S. Martin passed away after a yearlong illness. Two years later in 1960, B.B. Martin, now controlling owner, dissolved the team completely. Shortly thereafter, the Negro League didn’t exist, though historians can’t pinpoint the exact date it all came to an end. Thus, the Memphis Red Sox and the rich history of Negro League baseball ceased to be.

Notable Players

On top of those previously mentioned, quite a few big names passed through the Memphis roster in 37 years. Satchel Paige, a Hall of Fame pitcher whose career spanned five decades, played a single game for the Red Sox in 1943. At 37-years-old, Paige pitched for five innings, throwing seven strikeouts and allowing zero hits. Paige would go on to play in the majors for six seasons, his last game coming in 1965 at the age of 59.

RELATED: Coin to honor 100th anniversary of Negro League baseball gets bipartisan support in Congress

Despite never playing in the major leagues, two Memphis Red Sox players, William “Willie” Hendrick Foster and Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, were inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

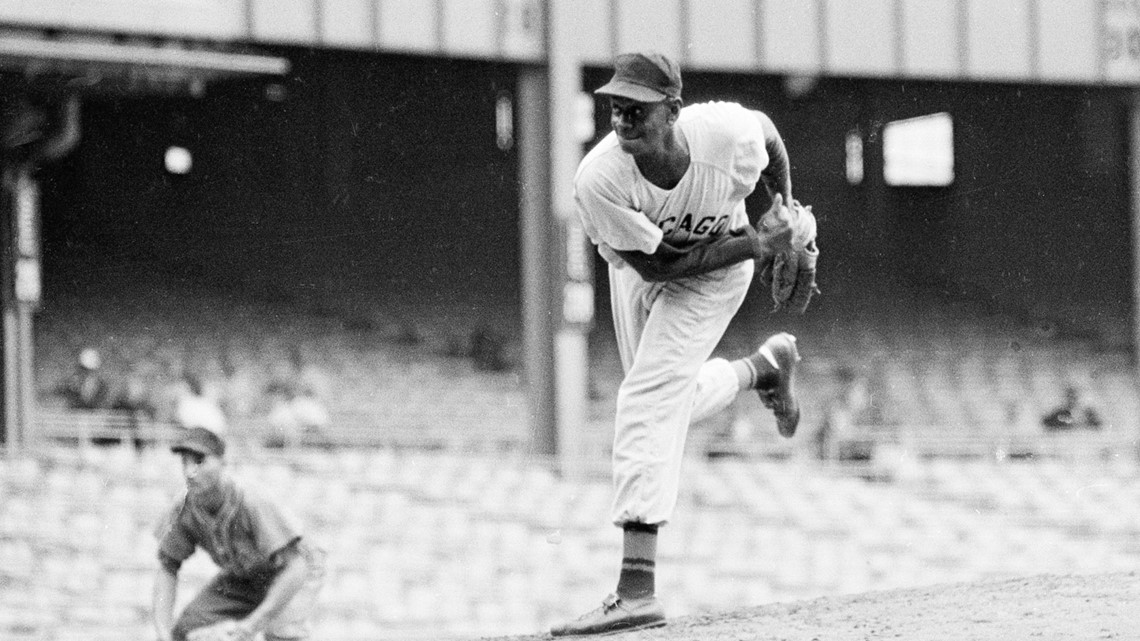

Willie "Bill" Foster was the half-brother to Rube Foster, a Hall of Famer, founder of the Negro National League and owner of the Chicago American Giants from 1911 to 1926 during the teams most successful years. Foster was a star pitcher for the Red Sox in 1923, 1924 and 1938. He even pitched a no-hitter against an independent Hot Springs ballclub in his time with the Red Sox. Foster joined his half brother in the Hall of Fame with his induction in 1996.

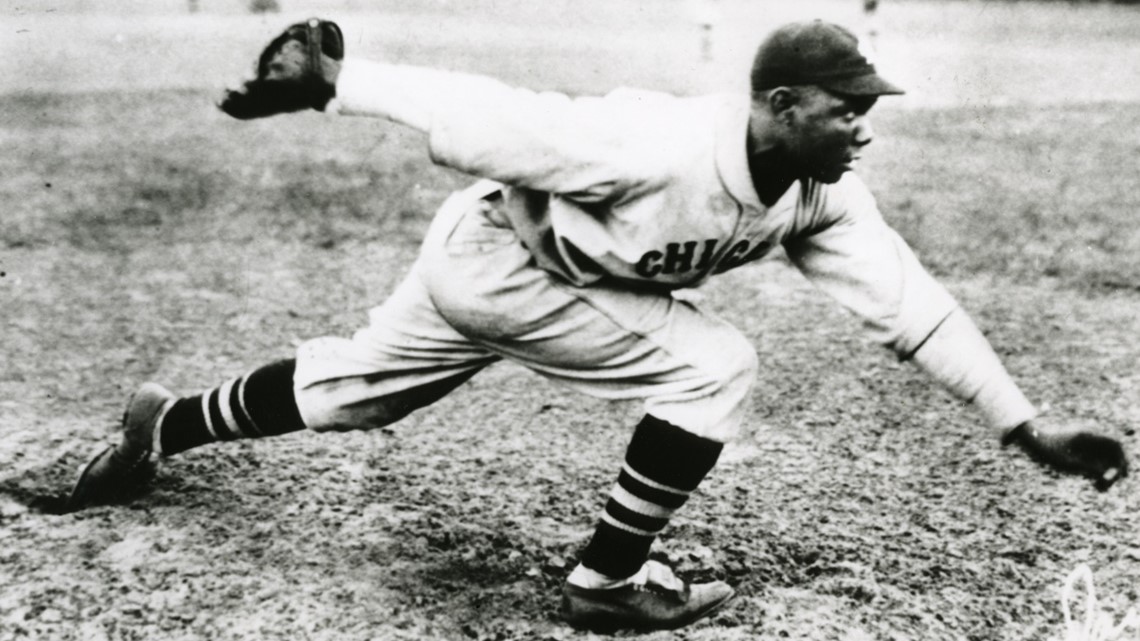

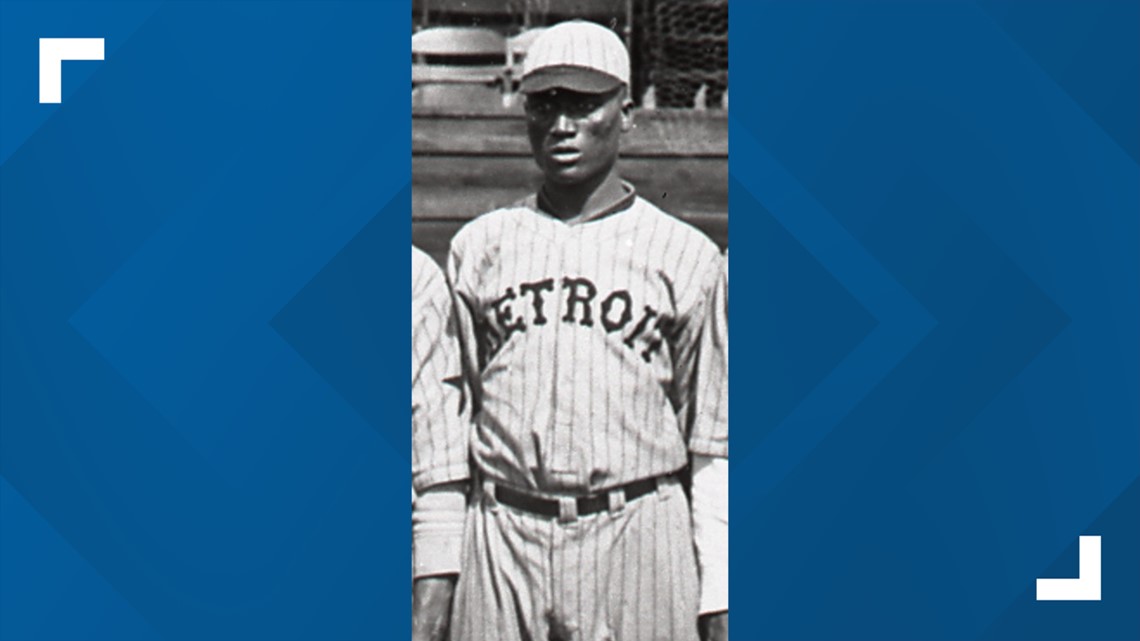

Nashville native Norman "Turkey" Stearnes, who earned the name for his strange running style, was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2000. Stearnes was only with Memphis for the 1922 season but went on to have a successful 13-year career playing first base, left field and center field.

A different kind of Hall of Famer started and ended his baseball career on the Memphis Red Sox roster. Charley Pride, the Country Music Hall of Fame singer, not only had twangy voice, he also had an arm for pitching. Pride caught the eye of the Red Sox pitching against them on a sandlot team. He would try out for the roster twice, and on his second attempt, earned a spot in 1952 at 18-years-old.

Pride bounced around the country, playing for both Negro and minor league teams, before ending his baseball career right back in Memphis in 1958. During his time with the Red Sox, the music industry was calling Pride's name. He even recorded a few songs at Sun Studio while on the roster. Eventually, he’d go on to trade in his glove for a guitar, and it seems things worked out for him—touting 36 No. 1 hit singles and 25 million records sold worldwide.

Remembering the Memphis Red Sox

Very little remains of the Memphis Red Sox.

Martin Stadium was demolished in 1961 shortly after the team dissolved, leaving very little physical evidence of the team’s existence. You can find a historical marker on E.H. Crump Boulevard where the ballpark once stood, but that’s about it. Besides those who have a deep knowledge of Memphis’ baseball history, not many even know the team existed.

There is hope that the legacy of the Memphis Red Sox will live on. Back in 2016, the Redbirds hosted a Memphis Red Sox throwback night to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the National Civil Rights Museum. Jack Keffer, the Communications and Public Relations Manager for the Memphis Redbirds, said the team is considering doing more Red Sox nights in the future.

In early 2022, Minor League Baseball launched its own initiative, known as The Nine, to connect with Black communities. The Nine, named after the number Jackie Robinson wore in his one season in the minor leagues, is “specifically designed to honor and celebrate the historic impact numerous Black baseball pioneers made on the sport” as well as diversify the sport, according to the MiLB website.

Efforts to reach out to Black communities by the MLB are increasingly important as the league recorded its lowest percentage of Black players in nearly 40 years at the start of the 2022 season. According to a UCF study, Black individuals make up only 7.2% of the MLB, the lowest percentage since the report was started in the mid-1980s. That percentage has followed a steady decline since the early-2000s.

The MLB is making an effort to get Black Americans involved in the sport they were excluded from for decades. In 2020, on the 100-year anniversary of the Negro Leagues, the MLB announced they would recognize Negro League players as major leaguers. Simply put, Negro League statistical records would be seen as MLB records. The same season, the MLB hosted a series of games honoring the Negro Leagues.

In a city like Memphis, there’s no shortage of Black pioneers. The Red Sox are no exception. From the team's inception to its quiet end, owners and players alike broke boundaries. Memphians, you know; we're a city built on not only persevering but thriving in times of hardship. The Memphis Red Sox are an emblem of this city’s unshakable, industrious attitude that lives on today.