MEMPHIS, Tenn. — “That's was the beauty of it, to see a kid and how excited he was to learn how to swim.”

A sight that for the black community is not often seen.

According to the CDC, drowning is the second leading cause of death for children ages 1-14, car accidents being the leading cause.

The CDC also reported that black children ages 10-14 are nearly 8 times more likely to drown than white children, other studies tie this directly to racial inequality.

However, that was not the case for a group of friends from south Memphis.

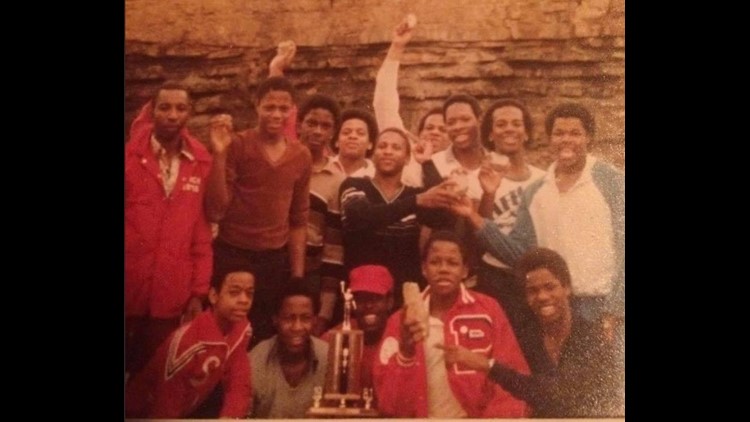

“I got involved in 1973, or championship run started in 69,” said Keith Smith.

Not even a full year after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated not far from where Smith and his friends lived, the Pinehill swimming legacy began.

Although segregation was illegal at this point, blacks and whites very rarely intentionally crossed paths.

“The city was divided up at the time. You had all-black teams swimming against all-black teams. And you had all-white teams swimming against all-white teams. And we would all convene in the city championship,” said Smith.

Due to separatism in the late 60s and early 70s, most black children who swam competitively could only swim during the summer.

“We swam against white teams that swam year-round. They had inside pools they had access, we as black kids didn’t have that access,” said Smith.

However, no matter the disadvantages, the guys of Pinehill had coaches like Walter Casey who made sure, no matter the competitor, they were ready to compete.

“We would actually practice in full clothing. We would have sweatshirts on, jeans, boots, shoes, whatever you had but that was actually to make us faster,” said Smith.

And they were faster.

From 1969 until 1974, the Pinehill swim team won city championships with ease.

But in ‘75, the team was tied with an all-white Fox Medows team and the title rested on the final event, diving.

A young Fox Medows diver completed a flawless pike one.

“She came straight up and down, and got all ten’s and one nine,” said Keith.

Putting the pressure on Pinehills’s diver, Tony Jones to score a perfect 10 to win for the seventh year in a row.

Attempting the pike two, flipping twice from the highest board.

“I remember doing the two, and that’s how I got all ten’s,” said Jones.

That year and the next two, the all-black Pinehill swim team continued to be city champions, a run that last a total of nine years consecutively, ending in 1977.

Although a distant memory now, many of the swimmers still swim today.

Alonzo Holt explained how important community centers are for children to have somewhere safe to go and stay out of trouble, as they did.

“We need somewhere to go, our kids need somewhere to go. Pinehill Park, Pinehill swimming pool, and Pinehill community center would mean a lot today. It’ll mean something as far as helping the next generation and I believe that,” said Holt.