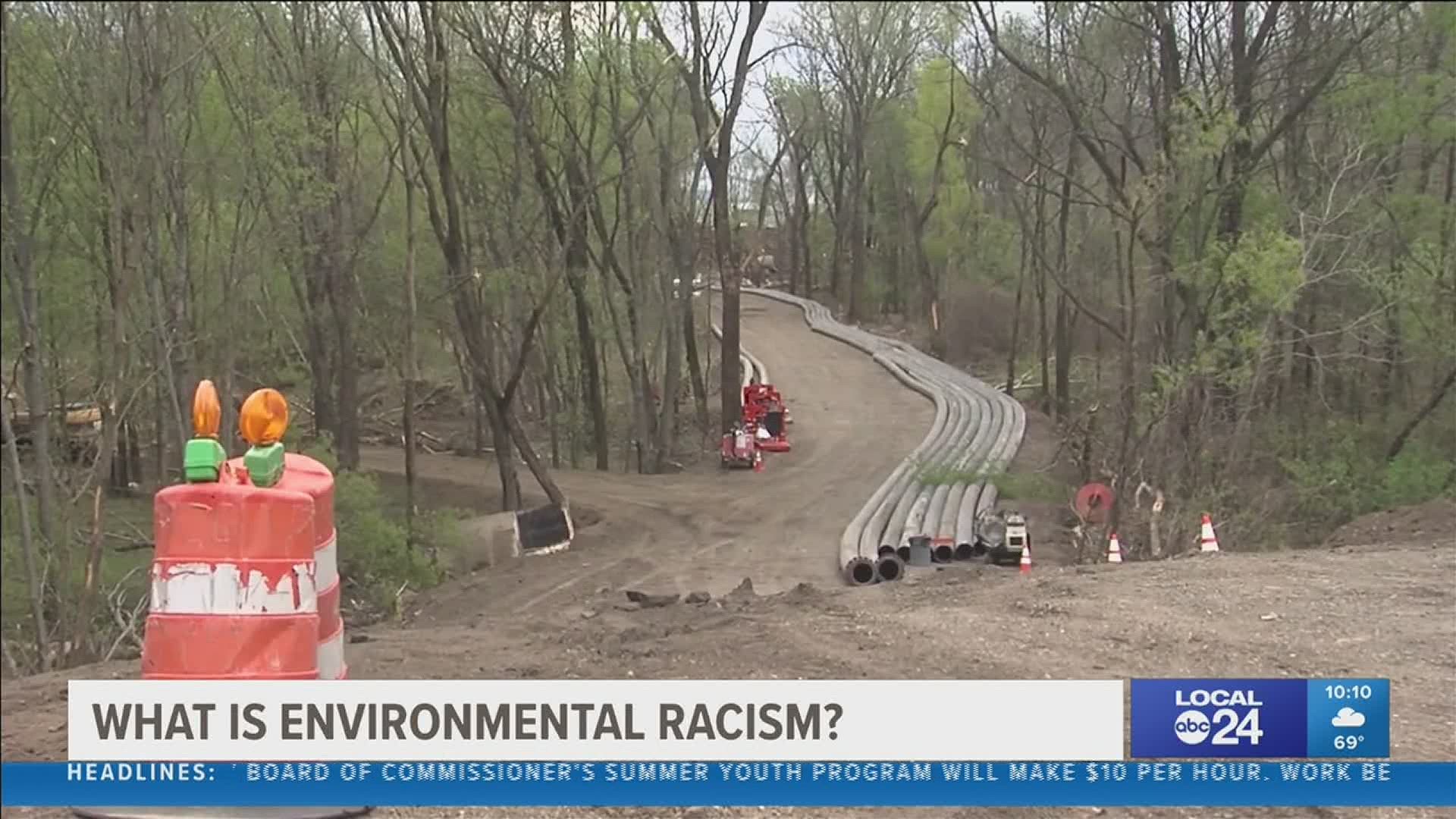

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — Today, the Memphis City Council approved a resolution opposing the Byhalia Pipeline. While the vote was favored by many, the entire controversy brings up the issue of environmental racism.

Local 24 News Reporter, Brittani Moncrease, takes a closer look as to what that actually is.

For Iseashia Hardaway Thomas, curiosity started with a picture published in MLK50.

“It was a picture of the house that I grew up in. My uncle was standing in between the trees and the first thing I saw was eminent domain,” said Hardaway Thomas.

Generations of the Hardaway family grew up in that Boxtown home.

“It said that that particular area is four times greater to have cancer than the national average. I was angry when I read that,” said Hardaway Thomas.

She is angry because her grandfather, grandmother, aunt, and uncle all had some form of cancer. Her mother died at just 57-years-old from the illness.

That anger brought Hardaway Thomas to learn of a new term called environmental racism.

“I went back to my childhood and how I would be so excited when we come around I-55 coming from downtown and the flames would be lit on that plant,” said Hardaway Thomas. “We would be so excited to see it as a kid not knowing that it was suffocating the neighborhood.”

What is environmental racism and is it a real thing?

“It most certainly is a thing,” said Dr. Kimberly Kasper, Rhodes College Assistant Professor. “It’s basically just a way minority groups, communities of colors are also dealing with just an overtly burden basically with a disproportion amount of hazards usually health hazards.”

Such hazards include waste facilities, mold, lead, and the fight against the Byhalia Pipeline.

“In essence, all of those things are decreasing the quality of life of the individuals and community members within these specific locations,” said Hardaway Thomas.

Why are these minority communities a target?

“Larger corporations will place their facilities in lower socioeconomic neighborhoods and communities thinking that people won’t fight back or they don’t have the resources to fight back,” said Dr. Kasper. “The fight has to come from a grassroots component.”

That is why Hardaway Thomas continues her fight against the pipeline.

“Even as bad as I’m hurting and feeling betrayed by a place I love so much, I still love this place,” said Hardaway Thomas. “How can you love a place that has taken basically your mother from you?...The fabric of my being is everybody deserves life. Everybody deserves to be treated right.”