In May 2022, former Virginia Tech football player Isimemen Etute was found not guilty of second-degree murder in the 2021 death of Jerry Smith, a gay man who Etute initially believed to be a woman based on Smith’s Tinder profile.

People online claimed it appeared that Etute had used the gay or trans panic defense, which is a legal defense that claims a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity/expression is to blame for a defendant’s violent reaction.

In response, a tweet with hundreds of shares claims that “the gay/trans panic defense isn’t banned in the overwhelming majority of states.”

THE QUESTION

Is the gay and trans panic defense still legal in the majority of U.S. states?

THE SOURCES

W. Carsten Andresen, Ph.D., St. Edward’s University criminal justice professor who conducted a study on LGBTQ+ panic defenses over 20 years

Ashley Korslien, anchor and reporter for television station KGW who produced the “Should Be Alive” podcast, which explores the murder of a transgender teen that inspired a LGBTQ+ panic defense ban in Washington state

THE ANSWER

Yes, the gay and trans panic defense is still legal in a majority of states.

WHAT WE FOUND

The gay and trans panic legal defense is a legal strategy that asks a jury to find that a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity/expression is to blame for a defendant’s violent reaction, including murder, according to the LGBTQ+ Bar, an association of legal professionals and organizations that promote justice for the LGBTQ+ community. The LGBTQ+ Bar refers to this as the “LGBTQ+ panic” defense to include violence against LGBTQ+ people who do not identify as gay or transgender.

No state recognizes the LGBTQ+ panic defense as a free-standing defense, the UCLA School of Law’s Williams Institute, a research center on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy, said in a 2021 report. Instead, the Williams Institute report and the American Bar Association (ABA) say the LGBTQ+ panic defense is used to bolster the defendant's defense claim.

There are three defenses the LGBTQ+ panic defense is paired with:

Defense of insanity or diminished capacity: argues that the victim’s LGBTQ+ identity is to blame for the defendant’s breakdown into a “panic”

Defense of provocation: argues the victim’s proposition of a “non-violent sexual advance” provoked the defendant to kill them

Self-defense: claims that because of the victim’s LGBTQ+ identity, the victim must have been about to harm the defendant

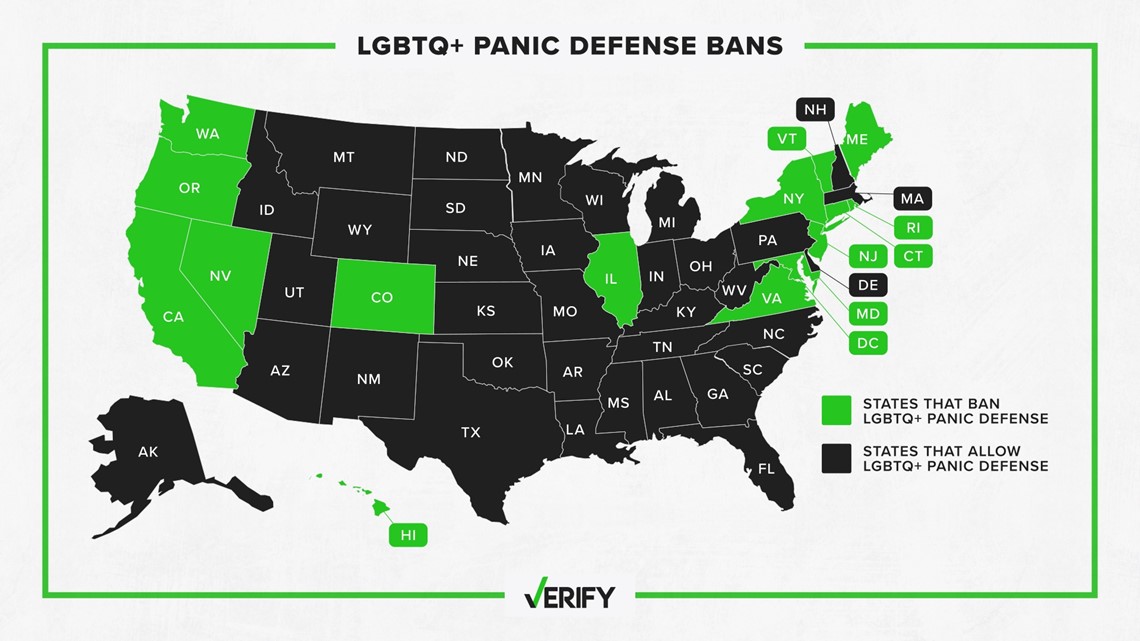

In 2013, the ABA issued a unanimous ruling calling on governments to prohibit the use of such defenses. Since then, 15 states and Washington, D.C. have explicitly prohibited the use of the defense, according to the nonprofit Movement Advancement Project (MAP). It is not banned in 35 states and five territories, and it isn’t banned at the federal level, either. According to MAP, 57% of the American LGBTQ+ population lives in states where the defense isn’t banned.

How often are LGBTQ+ panic defenses used?

W. Carsten Andresen, a criminal justice professor at St. Edward’s University in Texas, identified and studied 99 cases with 101 defendants who used a LGBTQ+ panic legal defense in America between 2000 and 2019.

According to Andresen’s research, 42 of those defendants raised provocation defenses and 59 raised self-defense arguments. None of the defendants raised insanity or diminished capacity defenses.

The LGBTQ+ panic defense rarely amounted to full acquittal for the defendants; only one of the defendants who raised a provocation defense and five of the defendants who raised self-defense arguments were acquitted. Instead, Andresen found the goal of such defenses was often to reduce the severity of their charges.

Andresen found 30 of the 101 defendants were granted a reduction of some kind to their charges, and 12 of the 93 defendants facing murder charges were convicted of manslaughter instead of murder.

Andresen wrote that he planned a future analysis of the cases which saw reduced charges to pinpoint the role the LGBTQ+ panic defense played in the reduction of charges in each case.

Is the LGBTQ+ panic defense always obvious when used in court?

Defendants don’t tell the courtroom they’re using a LGBTQ+ panic defense, and they often try to mask that they are using one.

“They're absolutely going to be subtle about it,” Andresen said in an interview with VERIFY. “Defense attorneys are not going to come right out and say, ‘Hey, I'm going to use race or ethnicity,’ ‘Hey, I'm going to use sexism,’ ‘Hey, I'm going to use homophobia or transphobia.’”

And while sometimes a defense lawyer might be overt in making the connection between the victim’s LGBTQ+ identity and the defendant’s murder, the defense might instead talk about the victim’s identity and how it affected the defendant’s mental state as if it was unrelated to the defendant’s violent reaction.

“There can be undertones that a defense attorney might use in their language and how they portrayed the victim, or why their client, the defendant, killed the victim,” said Ashley Korslien, an anchor and reporter for VERIFY sister station KGW.

What do LGBTQ+ panic defense bans look like?

Korslien hosted a six-episode podcast series called “Should Be Alive” that investigates the 2019 murder of Nikki Kuhnhausen, a transgender teenager in Vancouver, Washington. David Bogdanov was charged with Kuhnhausen’s death and used the trans panic defense during his trial. The defense failed for Bogdanov, and he was sentenced to 19.5 years for second-degree murder and malicious harassment.

Kuhnhausen’s murder prompted Washington state to pass a law banning LGBTQ+ panic defenses. Even so, such a defense was permissible in the trial because the law had not yet taken effect at the time of the murder. A similar situation played out in Virginia, where the Isimemen Etute case took place.

The Washington law, called the Nikki Kuhnhausen Act, says a defendant does not suffer from diminished capacity because of a victim’s LGBTQ+ identity, and a person is not justified in using force against another based on a victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

The law does not clarify what the courts should do to prevent someone from using a LGBTQ+ panic defense.

Many of the bans in other states work like Washington’s, Andresen said, where the state makes it explicit to the judge and the jury that certain justifications are not permitted, or where the state says the defense is not allowed to attack the victim’s character using their sexual orientation or gender identity. An example of the latter — a law that forbids evidence used to attack the victim’s character based on their LGBTQ+ identity — is in Colorado’s law banning LGBTQ+ panic defenses.

“The state is sort of stating its values by saying, ‘We know this is a problem. And we don't agree with it, we'd like it to stop,’” Andresen said.

But given the often subtle and indirect nature of LGBTQ+ panic defenses, Korslien says not everyone will agree on what constitutes such a defense.

“That's what's really tricky about this,” Korslien said. “It sometimes depends on who you ask — you might talk to a defense attorney, a judge and a prosecutor, and they may all have different ideas of whether a defendant was technically using the panic defense.”

Typically, these bans are enforced when the prosecution first identifies a panic defense, and then the judge determines whether the argument or evidence is such a defense, Andresen and a Washington state prosecutor said.

Even in states where no laws forbidding the LGBTQ+ panic defense exist, prosecutors can still try to fight them by making a case to the jury that the evidence presented is homophobic or transphobic, and does not excuse the actions of the defendant, Andresen said.

But because these laws rely on the discretion of individuals, namely the prosecution and the judge, it’s possible for a defense to still get away with a LGBTQ+ panic defense in a state where it’s banned. Andresen said prosecutors’ unfamiliarity with LGBTQ+ stereotypes, prejudices and tropes can leave them ill-equipped to actually shut down these defenses — ban or no ban.

“There needs to be legal education and awareness of LGBTQI+ victims,” Andresen said in a press release for his study of panic defenses. “Prosecutors don’t always know how to respond to tropes and stereotypes. Simply put, the blind spots in the criminal justice system make it harder for certain victims to get justice.”

Andresen said, regardless of the success of LGBTQ+ panic defenses in individual cases, the fact that they can be used to justify violent crimes at all sets a dangerous precedent by normalizing violent reactions to people’s LGBTQ+ identities.

“We don't want to send that message to society,” he said.

More from VERIFY: ‘Nobody talks about it': Understanding the rise in youth suicide